Published 7-06-2013, 10:05

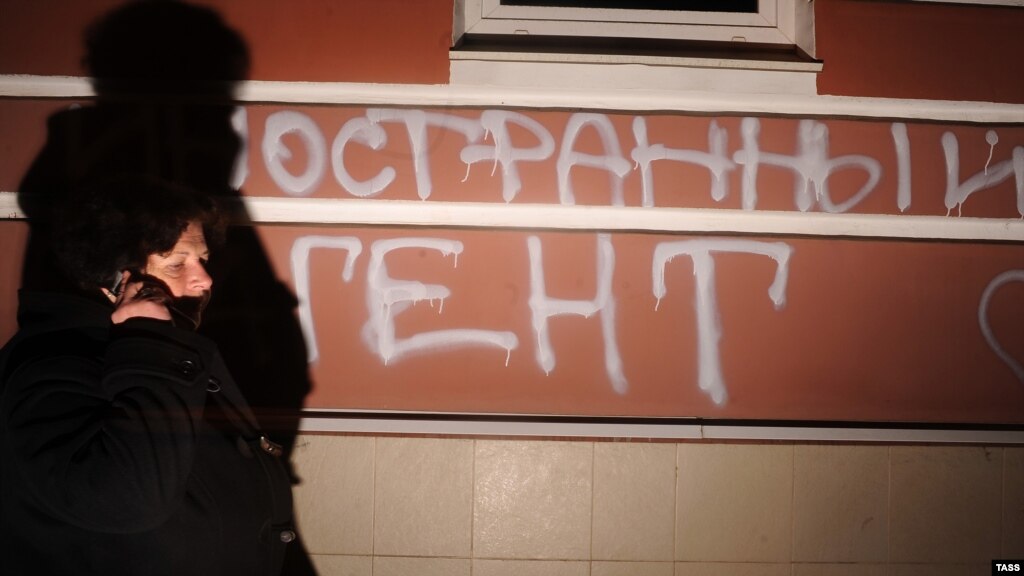

Russia’s law on "foreign agents”, which

entered into force last November, is seen by its critics as yet another turn of

screw by the repressive regime of President Vladimir Putin. The hastily drawn

up legislation introduces the concept of an NGO "performing the functions of a

foreign agent”; specifically, it targets non-commercial organizations that

receive at least part of their funding from foreign sources and participate in

"political activity” in the Russian Federation, including in the interests of

their foreign benefactors. Such activity is defined as including the "shaping of public opinion” and "influencing

decision-making by state bodies in order to change state policy”.

Russia’s law on "foreign agents”, which

entered into force last November, is seen by its critics as yet another turn of

screw by the repressive regime of President Vladimir Putin. The hastily drawn

up legislation introduces the concept of an NGO "performing the functions of a

foreign agent”; specifically, it targets non-commercial organizations that

receive at least part of their funding from foreign sources and participate in

"political activity” in the Russian Federation, including in the interests of

their foreign benefactors. Such activity is defined as including the "shaping of public opinion” and "influencing

decision-making by state bodies in order to change state policy”.

The law subjects these NGOs to a more stringent regulatory regime. Before launching their work in Russia, they must apply to be entered into a newly created "registry of foreign agents”. They are also required to report more frequently than other NGOs on their managerial structure and finances, and they must include the designation "foreign agent” in all their published materials.

Not surprisingly, no NGO in Russia has voluntarily registered as a "foreign agent”. Rather, eleven of them have appealed to the European Court of Human Rights while at the same time seeking – and obtaining – moral support for their opposition to the new law from the Council of Europe and the European Union.

Of the dozens of NGOs the Russian authorities have subjected to investigation, the election watchdog Golos is the first to have been fined (in late April) for failing to register as a "foreign agent”. In mid-May the Levada Center, the highly respected independent opinion research agency, was ordered by the public prosecutor to cease publishing its research until it declares itself a "foreign agent”. Lev Gudkov, the director of Levada, argues that compliance with that order could lead to the Center’s closure. Although grants from abroad account for no more than 3% of its total budget, the label "foreign agent” would, according to Gudkov, make it impossible for the Center to carry out its research, for who would want to take part in a survey conducted by a "foreign agent”?

Besides, there are obvious difficulties with the law’s interpretation, such as what exactly constitutes "political activity”. And then there is the question of whether it is really necessary to deploy the loaded term "foreign agent” – with its obvious negative connotations and Stalinist-era echoes – implying that the NGO in question works for a foreign power against Russia.

So, on the one hand, the critics’ arguments that the purpose of the law is not merely to clampdown on activities assisted by foreign funding but to eliminate all independent activity in Russia appear justified. Indeed, the regime has increased state support for NGOs (through the Public Chamber and regional government funds), thus creating in effect yet another stratum of its "power vertical”.

On the other hand, the Kremlin’s position can be understood, certainly to an extent. The regime is focused on preserving Russia’s political stability, which has been hard won following the implosion of the state and the economy in the immediate transition from Communism. The wave of public demonstrations following Putin’s decision in late 2011 to return to the presidency has once again raised the specter of a Western-engineered "color revolution”. Indeed, in its major foreign-policy document published in February (the so-called Concept), the Kremlin explicitly warns the West against the use of "soft power” and the promotion of human rights to exert political pressure on sovereign states and destabilize their constitutional order. In short, the new law on "foreign agents” reinforces the message that Russia will not tolerate external interference in its domestic affairs and is determined to put a stop to any perceived meddling – even at the risk of damaging Russia’s incipient civic society.

Questions:

- •Is the regime over-reacting by imposing such draconian restrictions on NGOs?

- •Consensus, transparency and the rule of law constitute the foundation of democracy. Instead of flouting the "foreign agents” law, should the NGOs cooperate with the regime and/or at least try to seek a middle way over the issue?

- •Should the West urge the NGOs to adopt such a constructive stance?

The topic for the Discussion Panel is provided by Vlad Sobell,

The topic for the Discussion Panel is provided by Vlad Sobell, Editor, Expert Discussion Panel

Professor, New York University, Prague

Editor, Consensus East-West Europe

Expert Panel Contributions

Martin Sieff

Martin SieffChief Global Analyst, The Globalist

Russia is addressing real concerns in its NGO legislation

"Hard cases make bad law,” according to an old saying, and this is certainly true of Russia’s tough new law demanding non-governmental organizations register with the government. The furor over the law in Europe and America has opened up a massive new chasm between Russia and the West when it is in the true long range interests of both sides to learn to understand each other better, and cooperate more.

The current generation of leaders, policymakers and pundits across Western Europe and the United States are not only ignorant of the broad sweep, and terribly hard-earned lessons of Russian history, they are also blithely ignorant of the appalling post-Soviet decade of the 1990s when more than 25 million Russians died premature deaths because of the collapse of living standards and social support systems.

However, Russian policymakers and the general public remember those terrible times well: Those traumatic memories explain why Russia's leaders are determined to uphold their "vertical,” the effectiveness and integrity of their central government, and why there are determined not to let Western-based NGOs, or Russian-based ones that are inspired and guided by Western mentors, from transforming their state along lines approved by editorial writers in Washington, New York, London and Brussels.

At the heart of the row over the regulation, or lack thereof, of NGOs in Russia is the classic debate between Westerners and Slavophiles that goes back at least to the 1840s. Had Alexander Solzhenitsyn still been alive, one can easily predict he would have unhesitatingly backed the Kremlin on the issue, just as Fyodor Dostoevsky would have done in the 1860s. On the other side of the debate, Russian liberals today are the clear heirs of Alexander Herzen.

But what gives teeth and weight to the Russian government’s line on NGOs today is that it is not just repeating ancient justifications for authoritarian rule that were wheeled out 170 to 150 years ago. The Russia of Vladimir Putin and Dmitri Medvedev is manifestly not the isolated, impoverished and ferociously disciplined Hermit Empire of Tsar Nikolai I. The Russian government today is not reacting to imaginary or prophetic fears about a terrible revolution half a century in the future. It is responding to the vivid, fresh memories of a "time of troubles” that ended only in 1999, less than 15 years ago.

The actions of liberal, pro-human rights NGOs in Russia who have refused to accept the terms of the new law have been catastrophic to their own cause. Eleven of them have appealed to the European Court of Human Rights while at the same time seeking – and obtaining – moral support for their opposition to the new law from the Council of Europe and the European Union.

This move guarantees two things: First, it confirms the government in its view that all unregulated, NGO activity in Russia is potentially and probably subversive in nature. Second, far from strengthening the forces of democracy, pluralism and tolerance, it discredits them. The 11 NGOs may now seem in the eyes of much of the Russian public as trying to undermine the nation and seeking the protection of hostile outside powers. Liberal groups critical of government policies in the United States over the past half century have often fallen into this same trap.

Western governments and international human rights organizations need to initiate a series of dialogs with the Kremlin rather than simply descending into a shouting match with it. Their leaders and spokesmen need to learn and understand the legitimate concerns of the Russian government based on the appalling experiences and costs of the country’s recent history.

Western policymakers also need to understand that the Kremlin’s fear of a destabilizing Western-engineered "color” revolution are born of real observations and experiences, and are not groundless fantasies. Such revolutions did overthrow the previous governments of Ukraine, Georgia and Kyrgyzstan during the past decade. They led to an era of corruption, impoverishment and shameless looting in Ukraine, upheaval, civil clashes and eventually even war with Russia in Georgia, and to unprecedented ethnic riots in Kyrgyzstan in which many hundreds of innocent ethnic minority Uzbeks were killed.

Russian policymakers and millions of people in Russia fear that a similar revolution in Russia could lead to a new "time of troubles” of powerlessness, economic ruin and universal suffering that could cost millions of innocent lives. Western leaders and NGO officials who lecture Russia have shown no signs at all of understanding this history: They appear blithely ignorant of it.

Russia’s concern over the unregulated activities of international NGOs is shared by other governments, democratic and undemocratic, that together rule well over one third of the population of the world, and more than three times the combined populations of the United States and the European Union. Western leaders need to address this growing "crack in the world” and seek constructive dialogs and cooperation with the governments on the other side of it, including Russia’s. This would do far more good for ordinary people everywhere than indulging in more childish public rebukes.

Frank Shatz

Frank ShatzColumnist

The Virginia Gazette

The term ‘foreign agent’ is unhelpful

While contemplating the question posed by the US-Russia.org. Expert Discussion Panel: Is Russia’s ‘foreign agents’ law justified? I recalled my first encounter with Robert Gates, the former U S Secretary of Defense.

Gates at that time served as Director of the CIA. He was visiting his alma mater, the College of William & Mary, in Williamsburg, Va., to deliver a lecture at the Law School. He gave a highly polished Washington insider’s view of global politics, talking about the break-up of the Soviet Union and the implications of that momentous event.

During an interview following the lecture, I asked him, half in jest: "Will we ever learn from you whether Gorbachev was a CIA asset, as his enemies in Moscow are asserting?”

Gates replied with a grin, "No, you won’t read anything of this sort in my autobiography. But there may be a chapter describing my first encounter with Gorbachev. It took place in the Kremlin. We were sitting across from each other at the conference table. Gorbachev pointed his finger at me and said reprovingly, ‘I know all about you, Mr Gates, and how distrustful you are of us. But you will be proven wrong. And remember my words. Because of your attitude, you will lose your job’.”

"Alas,” said Gates with a wry smile, "Gorbachev was the one who was out of a job.”

All this seems relevant in view of the controversy surrounding Russia’s law on "foreign agents.” It tends to poison the atmosphere, without solving any problem.

Nicolai N. Petro

Nicolai N. Petro Professor, Department of Political Science

University of Rhode Island

The NGO law reinforces Russia’s adherence to Western practice

The short answer is – yes. Yeltsin’s 1996 law "On Non-commercial Organizations” (which, by the way, already provides for future legislation to regulate "foreign agents”) was certainly due for an overhaul. While the amendments passed last November are far from perfect, they do pursue a valid social objective – to increase the transparency of foreign funding for NGOs that are engaged in "political activities aimed at influencing the adoption of government decisions, at changing their policies, and the shaping of public opinion to these ends” (Article 2, point 6, as amended).

One can certainly make the case that this formulation is too vague, but that is an issue for Russian courts to decide. Those who suggest that Russian courts pliantly serve government should update their information, since in reality Russian courts have ruled against the government and in favor of plaintiffs in over 70% of the civil cases brought before them in the past eight years (see Mikhail Barshchevsky, "Sudya po vsemu: Vyacheslav Lebedev – Ne grazhdanin, a chinovnik dolzhen dokazat; v sude svoyu pravotu,” Rossiiskaya gazeta, February 19, 2013; and Yuri Kolesov, "The Shadow of Judgement: Russian Citizens Distrust The Judicial System." Vremya novostei, October 19, 2004, cited in JRL #8416).

The proper purpose of such laws – to increase the public accountability of political actors – is recognized in every Western country. It is therefore entirely appropriate for Russia have something similar in place. This does not deviate from Western practices; it reinforces Russia’s adherence to them.

Setting aside, for a moment, the self-serving rhetoric of the few organizations actually affected by this law, anyone truly concerned about the public interest must surely be troubled by their concerted efforts to evade such accountability. In the long run, this can only undermine respect for the law, harm the domestic standing of Russian NGOs, and weaken the independence of Russian civil society.

Anatoly Karlin

Anatoly KarlinDa Russophile

What's good for the goose is messed up by the gander

Okay, let's get one thing clear from the get go: The Russian law requiring NGOs to declare themselves "foreign agents" if they engage in political activities and receive financing from abroad, is not illegitimate. At least, not unless you also consider the US' Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) - which does practically the same thing - to be also illegitimate.

Which is just fine, mind you! But only as a universal value judgment, and not as a tool to selectively beat Russia over the head with.

Or you can shrug it off as paranoia. But bear in mind that just because you're paranoid doesn't mean they're not out to topple you. The color revolutions were in significant part funded from abroad, and there has recently appeared witness testimony (backed up by video footage) of Udaltsov, one of the most prominent leaders of the street opposition, receiving money from a Georgian politician. So there is a case to be made that a certain amount of paranoia is necessary to preserve Russia's sovereign democracy.

As such, a foreign agents law is not a bad idea per se, at least assuming it is applied rigorously but fairly. That may be too much to expect of Russians, though.

Problem is that said paranoia, while healthy in modest doses, may end up impinging on the "democracy" part of sovereign democracy. While labeling a crane reserve as a foreign agent might be more farce than substance (if so then what would that make the "alpha crane," that is, Putin? - as the Runet jibes go), the same cannot be said of the pressure applied to the Levada Center.

Foreign financing only accounts for 1.5-3% of its total, according to its director, Lev Gudkov. Furthermore, he argues, the political and sociological research that Levada does is not politics, period. Certainly that would appear to be the case in the US, where it is virtually impossible to imagine the Department of Justice going after PEW, Gallup, or Rasmussen if they happened to take a few contacts for foreigners.

So while the laws might be similar on paper, the Investigative Committee is taking a much, much wider interpretation of what falls under the rubric of politics. And I would say that this is not only unjust but ultimately, stupid.

Levada does not fudge its results. They typically fall in line exactly with those of FOM and VCIOM, the two state-owned pollsters - including on the most politically significant indicator, Putin's approval rating, which was an entirely respectable 64% as of this May. And while Levada does have an undeniably anti-Putinist editorial slant, this is arguably all the better – from the Kremlin's perspective – since it makes it seem to be "independent" and hence reliable in the West. FOM and VCIOM, as state-owned entities, would never be able to muster the same degree of credibility no matter the integrity with which they conduct their surveys.

From the meaningless police confiscations of Nemtsov's "white papers" (which are only ever read on the Internet) to the harassment that frightened the economist Sergey Guriev into exile in Paris, petty authoritarianism on the part of lower level police and investigators is one of the most reliable manufactories of the ammunition that the "anti-Russian lobby" in the West uses to take potshots at Putin.

Edward Lozansky

Edward LozanskyPresident, American University in Moscow

Professor of World Politics, Moscow State University

US should find better uses for its ‘foreign agents’ money

Predictably, the new "foreign agents" law has caused an outcry from both Russian recipients and Western donors of the cash to Russia's NGOs. For those of us who respect President Thomas Jefferson's fiat not to "meddle in the internal affairs of foreign countries," commenting on this law is not easy. However, America's heavy involvement in this sort of activity justifies such comments – at least morally.

To start with, a quote from former US Ambassador to Moscow James Collins, currently with the Carnegie Endowment: "Whether we like some Russian laws or not, we must respect them.” This is markedly different – to put it mildly – from statements by former State Secretary Hillary Clinton and current US Ambassador to the UN Susan Rice, both of whom have advocated finding ways of bypassing Russia's law on foreign agents.

Looking at the problem from a different angle, some interesting questions arise. For example, why should the United States, with its huge budget deficits and astronomical national debt, keep coughing up tens of millions of dollars to help Russian NGOs?

It is puzzling questions of this kind that leads Moscow to suspect that Washington has some hidden agenda, and it can cite cogent reasons to support that belief: in the past the West funded anti-Russia "color revolutions" in the post-Soviet space; at present, it spends huge sums on "soft power” to demonize Putin's Russia.

The next obvious question to be asked is this: What is to be done? I, for one, would prefer that we keep the money and use it for domestic purposes or for causes that might help improve US-Russia relations rather than worsen them. There are a million useful things that Americans and Russians could and should do together – such as expanding people-to-people contacts, educational and cultural exchanges, joint scientific research and even joint farming – why not?

Instead, America opts for a democracy-promotion crusade, which is not just cynical but also very dangerous. It nearly landed us in World War III when we backed Saakashvili's criminal regime in Georgia. It has created the unending chaos in the Middle East, the final outcome of which remains unpredictable. And it leaves America no moral ground to stand on. Consider the following: Russia with its democratic institutions – admittedly far from perfect ones – firmly in place is portrayed by the US as a monstrous villain; meanwhile sheikhdoms and kingdoms still stuck in the Middle Ages and run along sharia law lines are upheld as America's most reliable allies.

It would be useful to recall here that George W. Bush was all for democracy promotion because, he insisted, democracies do not start wars. That theory did not prevent him from ordering the invasion of Iraq with terrible consequences that continue ten years later and get worse by the day.

We are well aware, of course, that foreign policy and morality do not go hand in hand. Let us be cynical, then, and ask ourselves this question: What is in the best interests of the United States as a nation? Shall we keep pushing Russia around using all means available, including encouragement for and funding of an internal opposition that has low single-digit support among the country's population? Or should we search for and implement a mutually beneficial agenda?

It must be admitted, with regret, that at present the majority of the Washington foreign policy establishment prefers the former strategy – if strategy is the right word here. Those of us who favor the latter approach are in the small minority. Of course, only history will decide which group was right. But it is useful to remember at all times that goodwill is much preferable to ill will and endless strife.

Mark Sleboda

Mark SlebodaSenior Lecturer and Researcher

Department of International Relations and Centre for Conservative Studies

Sociology Faculty

Moscow State University

Russia must defend its civil society

Russia has every right, and indeed the Russian government has a duty, to limit the political activities of foreign governments and their proxy agents on Russian sovereign soil, that it feels are an undue influence on the nation’s political development. One of the most fundamental principles of the UN Charter and international law is non-interference in the domestic affairs of states.

Russia is far from alone in this regard. The US, itself, has nearly identical legislation – the Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA) in force since 1938, which the new Russian law is modeled on.

Claims that the implementation of the two bills is different are disingenuous. First, of course, the Russian law has just come into effect, so complaints about how it will be enforced at this point are just fear-mongering. Second, they ignore a wealth of cases that show how FARA in the US has been used selectively by different US administrations to target countries and political causes it disagrees with. Its use in 1982, later supported unanimously by the US Supreme Court, to force the Academy Award winning anti-war documentary, If You Love This Planet, and several other Canadian-funded political documentaries, to bear the label ‘foreign political propaganda’ in showings is just one such example.

Pro-Palestinian NGOs and activists have frequently been targeted by FARA, and even AIPAC, the pro-Zionist lobby in the US at one time became a target. Currently, the Hamas-linked Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), foreign funding of and foreigners associated with the Occupy Wall Street protest movement, and al-Jazeera English are all being targeted by their critics utilizing FARA to require disclosure and conspicuous labeling of foreign-funded political activities.

According to Lawrence Solomon writing in the Jerusalem Post, FARA, ”is but one part of an extensive legal framework that serves to limit the activities of the various types of NGOs that can operate in the US. NGOs are also regulated by tax law that bans tax-exempt charitable NGOs from any partisan political activities and, with minor exceptions, from activities promoting or opposing legislative efforts. These NGOs cannot receive funds for such political advocacy and they also cannot disburse funds abroad to foreigners for such political advocacy.” Many Islamic charities and NGOs, have likewise been banned from operating in the US, often under dubious allegations, under "War on Terror” provisions run amok.

US and other Western government funded NGO proxies and opposition movements have come into prominence and under fire over the last decade for the stealth pursuit of US foreign policy interests and interference in the domestic politics of countries around the world. This includes the short-lived Color Revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan, the Cedar Revolution in Lebanon, unrest in Thailand and Myanmar, and as the New York Times and Foreign Policy have reported, the uprisings of the so-called "Arab Spring” through support for groups such as the April 6th Movement.

This has led to a global backlash from the international community rightly enraged about the violation of their sovereignty with such impunity. It is far from just Russia that has adopted or is in the process of adopting legislation and measures to ban or curb the interference of US and Western funded NGOs in their domestic politics. In the last few years, India, Israel, Indonesia, Moldova, Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Algeria, Somaliland, Kenya, Eritrea, Belarus, Thailand, and Myanmar have all done the same. Since 1995 in Africa, over one-third of countries, have passed new laws, or tightened old ones, restricting foreign aid to NGOs and/or limiting the work of international groups. Indeed, no self-respecting country would allow such interference in their politics.

Critics of these laws targeting foreign funded NGOs engaged in politics charge that they are inhibiting the growth of or outright stamping out civil society in these countries, but is this really the case?

In Russia there are over 277,000 NGOs. The Russian prosecutor general’s office has identified just 654 of these that receive significant foreign funding. Of these it has chosen so far to audit just 80 NGO’s for compliance with the new law which requires registration and identification of NGO’s engaged in political work in civil society that receive funding from foreign governments. And out of these, only 30 foreign funded political NGOs have been determined so far to fall under the guidelines and must register as "foreign agents” and face greater accounting scrutiny in order to continue their work. Just 30 NGOs forced to register out of 277,000… How will Russian civil society ever recover from such a blow?

The law also only applies to NGOs that are involved in political work. Religious organization, and those NGO’s involved exclusively in science, arts, culture, health care, disease prevention, social security and support for individuals, protection of motherhood and childhood, social support for disabled persons, promoting a healthy lifestyle, environmental protection and conservation, and charitable or volunteer activity, are excluded and not affected by the bill at all, even if they do receive foreign funding.

Another criticism often leveled is that the designation as "foreign agents” has a more negative connotation in Russian than in English. Well, I for one would be happy to just have them labeled "lobbyists”, but that is not a native word in Russian. If the critics can propose another nomenclature, I think the government should consider changing it, as long as the public is still duly informed that a foreign government is paying to have those views and information presented to them.

And that gets to the heart of the matter - the fact that these NGOs are funded not by Russian citizens but by foreign governments and middlemen, and thus ultimately foreign citizens as taxpayers. Therefore they are not a proper representation of Russian civil society, but the civil society and government of some other country. As David Rieff wrote in the New Republic, "Government funding, as anyone who knows the first thing about how NGOs actually function, implies a measure of government control over where and how NGOs operate.” It is oxymoronic to even call an organization funded by a foreign government, a Non-Governmental Organization.

The US and other Western governments believe they had a right and a duty to promote and impose their liberal political and social values on the rest of the world. However, countless independent polls, surveys, elections, and research show that only about 5% of the Russian population share those liberal values and views. Russia is not a poor country. Russian charities, particularly religious ones, receive large amounts of donations from their own citizens. These liberal NGOs can’t find funding not because of a government crackdown or scared citizens, but because they don’t actually reflect the views of the Russian people and their own civil society. You can’t purchase a civil society in another country that better suits your needs.

The foreign government funding thus creates an uneven playing field, unnaturally and unfairly distorting actual Russian civil society and politics, in a country that is still finding its own social and political identity. Those NGOs and their staff are able to promote their views and politics full time on the dime of Western taxpayers, without having to spend any time collecting funds from their own citizens, as most NGOs around the world have to do.

A proposed Israeli law, reflecting this selectively partisan and ideological nature of Western government funding for organizations in other countries, calls for a 45% tax on foreign funding of NGOs, with the intention that those funds then be redistributed to all of the other native grassroots NGOs that aren’t funded, because they don’t promote liberal Western values and interests. This might be a good compromise to allow foreign NGO funding, but level and restore balance to the civil society playing field.

The US is not just sitting down and accepting the new laws which limit and curtail their meddling in Russian domestic political affairs. US State Department officials have quickly "pledged to maneuver around the Kremlin” and bypass the law. The Russian Foreign Ministry responded that, "We view the declaration made by the official representative of the State Department, Victoria Nuland, that the United States will continue financing individual NGOs within Russia via intermediaries in third countries, bypassing Russian law, as open interference in our internal affairs”.

Russia must, therefore, continue this high-stakes game of "whack-a-mole” to block US interference and challenge to its sovereignty for the preservation of its own civil society and political development.

Patrick Armstrong

Patrick Armstrong Analysis,

Ottawa, Canada

Russia’s NGO law is an act of self-defence

How one reacts to Russia’s NGO law depends on what one thought those NGOs were doing in the first place. If they were disinterestedly and objectively advocating for and monitoring universal human rights, then the Russian law is objectionable. But if they were functioning as an arm of a foreign country’s policy then the Russian law must be seen as an act of self-defence.

Which leads us to the Russian law’s model: the American Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938. This act is still in force and has a section of the US Department of Justice charged with its enforcement. Note that the official description has many of the words that opponents of the Russian act claim to find so offensive: "agents of foreign principals”, "political or quasi-political capacity” "foreign agents” "Counterespionage” "National Security”. In 1938 the coming war was visible and there were many foreign interests that wanted to shape American public opinion. FARA was, therefore an act of self-defence.

Is the Russian act also an act of self-defence? Consider the reaction to Russia’s Duma election; despite results consistent with the findings of numerous opinion polls that Putin’s pedestal party was losing support but still commanded half the vote, US Secretary of State Clinton condemned the result instantly and the foreign-funded NGOs produced supporting "evidence” which did not stand up to later investigation (Vedomosti’s examination of Moscow results, the only serious examination of which I am aware, found nothing much). Consider Suzanne Nossel, smoothly moving between government and NGOs, committed to using "human rights” as part of the arsenal of US power. Consider a US official admitting that countries that don’t cooperate get "reamed” on human rights. It’s not "human rights”, it’s realpolitik.

Sceptics should ask themselves two questions: after all, it wouldn’t be the first time that reporting on Russia was stage managed. The first is why, in the endless think pieces about the Russian law, is the American law never mentioned? Second, why won’t the NGOs register under the law? In theory, once registered, they can still operate even if labelled, to quote FARA, as "agents of foreign principals”; shouldn’t they want to test whether this is true? Think how much stronger their case would be if they complied with the law and were shut down anyway. If they are, as they claim, objective seekers after truth, shouldn’t they be confident that the truth will out? Why are they folding without a struggle? Makes one wonder whether they are flaming out as a last obedience to their foreign masters because the truth is that they have no existence on their own. You should be suspicious: truthful reporting would mention that Russia is not alone with such a law and brave human rights supporters would forge on anyway. All this makes me more confident that the Russians are correct: it’s not human rights, it’s Nosselism.

Oh, and just as a matter of interest, Nossel has been associated with three NGOs: Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and, today, PEN (and not, by the way, to universal acclaim "Humanitarian imperialism” "cooption of the Human Rights movement by the U.S. government” and plenty more). In the last month the three have run pieces on Russia’s NGO law, AI still wants to free Pussy Riot and PEN has something on writers in Russia. But none of them, curiously enough, has anything to say about tax authorities harassing political opponents and legal authorities listening in on reporters’ conversations.

Which, a simple person would think, are quite serious human rights violations.

_jpg/250px-ElbeDay1945_(NARA_ww2-121).jpg)