Bryan Bender

Bryan Bender, who joined the Globe's Washington Bureau in 2001, covers the US military, global terrorism, the international arms trade, and government secrecy.

Accord worked to keep stockpiles secure

WASHINGTON — The private diplomatic meetings took place over two days in mid-December in a hotel overlooking Moscow’s Red Square.

But unlike in previous such gatherings, the sense of camaraderie, even brotherhood, was overshadowed by an uncomfortable chill, according to participants.

In the previously undisclosed discussions, the Russians informed the Americans that they were refusing any more US help protecting their largest stockpiles of weapons-grade uranium and plutonium from being stolen or sold on the black market. The declaration effectively ended one of the most successful areas of cooperation between the former Cold War adversaries.

"I think it greatly increases the risk of catastrophic terrorism,” said Sam Nunn, the former Democratic senator from Georgia and an architect of the "cooperative threat reduction” programs of the 1990s.

Official word came in a terse, three-page agreement signed on Dec. 16. A copy was obtained by the Globe, and a description of the Moscow meeting was provided by three people who attended the session or were briefed on it. They declined to be identified for security reasons.

Russia’s change of heart was not unexpected.

The Globe reported in August that US officials were concerned about the future of the programs, because of increased diplomatic hostilities between the United States and Russia. The New York Times reported in November that it appeared likely many of the programs would end.

On hand for the Moscow meeting were nearly four dozen of the leading figures on both sides who have been working to safeguard the largest supplies of the world’s deadliest weapons, according to the three-page agreement.

The group included officials from the US Department of Energy, its nuclear weapons labs, the Pentagon, and the State Department, and a host of Russian officials in charge of everything from dismantling nuclear submarines to arms control.

Specialists said the final meeting was a dismaying development in a joint effort that the United States has invested some $2 billion in and had been a symbol of the thaw between East and West and of global efforts to prevent the spread of doomsday weapons. An additional $100 million had been budgeted for the effort this year and many of the programs were envisioned to continue at least through 2018.

Since the cooperative agreement began, US experts have helped destroy hundreds of weapons and nuclear-powered submarines, pay workers’ salaries, install security measures at myriad facilities containing weapons material across Russia and the former Soviet Union, and conduct training programs for their personnel.

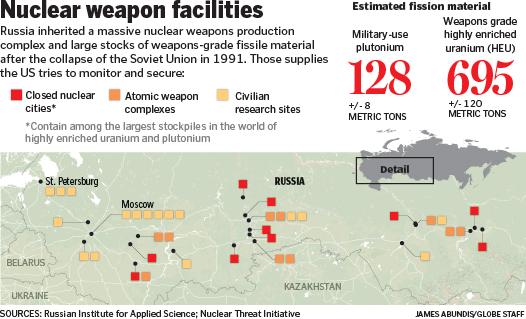

Officials said estimates of how much bomb-grade material has either been destroyed or secured inside the former Soviet Union is classified but insist the stockpiles are enough to make many hundreds of atomic bombs.

The work has been driven by deep concern that large supplies of nuclear material could be stolen by terrorists seeking weapons of mass destruction or diverted by underpaid workers susceptible to bribes.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s decision last year to invade the Ukrainian territory of Crimea and then back an armed rebellion in eastern Ukraine prompted a series of US and EU sanctions against Russia, which stirred fears that the era of nuclear cooperation was at risk.

Now security upgrades have been cancelled at some of Russia’s seven "closed nuclear cities,” which contain among the largest stockpiles of highly enriched uranium and plutonium, according to the official "record of meeting” signed by the sides in December.

The Russians also told the Americans that joint security work at 18 civilian facilities housing weapons material would cease, effective Jan. 1. Another project at two facilities to convert highly enriched uranium into a less dangerous form also has been stopped.

Lack of US funding and expertise also jeopardizes planned construction of high-tech surveillance systems at 13 buildings that store nuclear material, as well as a project to deploy radiation detectors at Russian ports, airports, and border crossings to catch potential nuclear smugglers.

A limited amount of cooperation will continue in other countries that have highly enriched uranium that originated in Russia. The two sides also will continue working on ways to secure industrial sources of radioactive material, which could be used to make a "dirty bomb.’’ The Russian decision will not affect inspections that both sides regularly conduct of each other’s active nuclear arsenals as part of arms control treaties.

But that is little consolation for those like Siegfried S. Hecker, one of the nation’s premier experts on nuclear weapons. Hecker, a former head of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, has traveled more than 40 times to Russia since 1992 as part of the joint security efforts. While he said vast improvements have been made in Russia’s atomic security since the end of the Cold War, "you’re never done.”

"They need continuous attention and international cooperation,” he said in an interview. "You cannot afford to isolate your country, your own nuclear complex, from the rest of the world.”

The Russian embassy in Washington, and the Russian State Atomic Energy Corporation in Moscow, did not respond to requests for comment. In the December document, the Russians said they are capable of securing their own nuclear facilities, out of Russia’s federal budget.

But a number of former US government officials and nuclear experts expressed doubts about the Russian pledge, pointing to recent economic troubles.

"The Russians say they are going to put a lot more of their resources into this,” said Nunn, who is cochairman of the Nuclear Threat Initiative, a Washington nonprofit that works to reduce the dangers of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. "That would be good news if they do, but with their economic challenges now and with the huge distrust built because of Ukraine and the deterioration of the ruble, the proof will be in the pudding.”

Another key architect of the programs, former Republican senator Richard Lugar of Indiana, who last visited some of the facilities in 2012, said he wonders if the Russians have the expertise needed to keep track of the vast amount of nuclear bomb material.

"The housekeeping by the Russians has not been comprehensive,” Lugar said in an interview. "There had been work done [with the United States] hunting down nuclear materials. This is now terminated.”

Some warn that the distrust on both sides could bleed into other areas, including arms control treaties.

"It’s important for the US and Russia to have nuclear security, but it is also important for us to believe we have nuclear security,” said Matthew Bunn, a weapons proliferation specialist at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University. "That’s hard to do just by saying so.”

US government officials, for their part, insist they are trying to make the best of it.

"We are encouraged that they statedmultiple times that they intend to finish this work,” said David Huizenga, who runs the nonproliferation programs at the National Nuclear Security Administration, an arm of the Department of Energy. Huizenga led the US delegation to Moscow last month.

But he said US officials still hope that the Russians will change their mind and restart a partnership that by most accounts has significantly strengthened global security.

"[It will be] harder to resurrect if we don’t actually engage in any meaningful way,” Huizenga said.