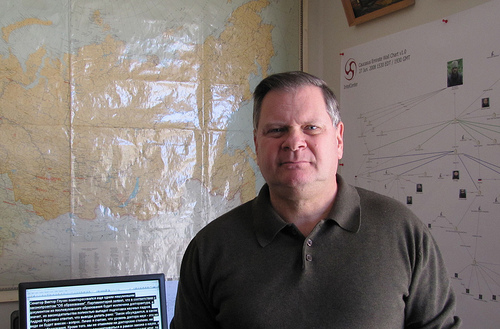

Richard Gowan

Richard Gowan is an associate director at New York University's Center on International Cooperation, and a policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Washington is contending with the blowback from its latest diplomatic gambit in the struggle with Russia. Last week, U.S. officials began to float the possibility of offering Ukraine defensive weapons to counter the latest advances by Russian-backed separatists in the east of the country. If this was a trial balloon meant to reassure Kiev, it had the unfortunate side effect of throwing some major European powers into overt panic.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Francois Hollande publicly declared their opposition to the plan and hurried to Moscow for talks with Russian President Vladimir Putin. There are plans for another meeting of the three powers, this time also involving Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, in Minsk this Wednesday.

Whatever Germany and France can deliver on the ground in eastern Ukraine, they have already effected three changes to the diplomatic landscape surrounding the conflict.

First, they have rehabilitated Putin as a serious interlocutor, a status that he seemed close to losing after the breakdown of previous Ukrainian cease-fires. Just weeks ago, Hollande and Merkel canceled a planned meeting with Putin in Kazakhstan. Merkel continues to question her Russian counterpart’s trustworthiness. But by going to Moscow,pre-empting a previously planned visit by the chancellor to Washington today, she and Hollande showed that Putin can always reclaim his seat at the table through the use of brute force.

Second, the diplomatic duo has also signaled to Putin that he is still unlikely to encounter any serious military consequences for his continued adventurism in Ukraine. Critics of arming Kiev point out that Putin knew this already: Russia could easily score all-out victory in Ukrainebefore U.S. arms reached the battlefield. But Putin and his generals will surely read the Europeans’ actions as signs of weakness.

Third, and most significantly, the Russians can also spy a clear division between Washington, Paris and Berlin that they can easily exploit again. Further bouts of aggression by Moscow and its allies in Ukraine will inspire American hawks, not least among congressional Republicans, to demand even firmer responses. Such calls for toughness will sow even worse dissension between the U.S. and its European partners, but also among European governments. The Franco-German rush to Moscow has already sidelined other European Union members—ranging from the United Kingdom to Poland and Sweden—that are less willing than Paris and Berlin to accommodate Putin.

As I wrote last week, it has long been clear that these relatively hawkish EU members would ultimately have to bow to Germany over how to resolve the Ukrainian crisis. But Merkel and Hollande’s gambit has sent a clear message to Putin: Whereas the EU and NATO have managed to cobble together common positions over Ukraine over the past year, these are liable to fall apart when the crisis escalates to a danger point.

If a mere trial balloon from Washington about arming Kiev is enough to make Berlin and Paris scramble for a political compromise, how would they behave if Russian armor appeared outside Kiev itself? Putin is said to think that European unity is a sham. The past week’s events will not have disabused him of this notion.

They will, moreover, presumably leave him optimistic about the chances of driving an even greater wedge between the U.S. and Europe’s leading powers, either during the current crisis or at some other opportune moment. It is striking that Germany and France appear almost as nervous about small-scale hypothetical American aid to Ukraine as they do about Russia’s actually existing large-scale intervention there.

While there are certainly good reasons to suspect that funneling arms to Ukraine can only complicate the conflict, the Franco-German response also seems to reflect deeper prejudices against U.S. influence in Europe. France has arguably shifted closer to the U.S. in recent years, partially because of the need to cooperate in the face of crises in Africa and the Arab world. But Germany’s affiliations are a source of concern.

As Hans Kundnani has argued, Germany’s strong economic and historical ties to Russia mean that "it may not have the stamina for a policy of containment” toward Moscow. The current edition of the—admittedly steadfastly pro-American—Economist warns that German decision-makers are relapsing into "endemic” anti-Americanismthat "affects everything from the West’s response to terrorism and Russian bullying to free-trade talks between America and the European Union.”

If this worrying trend proves irreversible, historians may scrutinize the past week’s developments as a pivotal moment when Germany moved away from U.S. influence. In this scenario, American commentators will surely berate Merkel for her pusillanimous disloyalty, and accuse Hollande of similar personality flaws.

But they will also ask why the U.S. chose to scare two of its main allies by floating the idea of arming Ukraine. As of now, this seems like a mismanaged attempt to satisfy the White House’s Republican critics and fire a shot across Putin’s bow. Yet it appears that its probable impact on European behavior had not been fully foreseen.

Unless, that is, U.S. President Barack Obama and his advisers actually floated the threat of escalating the Ukrainian conflict precisely to shove Berlin and Paris toward a new bout of dealings with Moscow. Obama has never hidden his desire to insulate his remaining time in office from foreign policy problems, of which he has a surplus already. The latest U.S. National Security Strategy, published last week, lambastes Russian aggression but also urges "strategic patience” in handling such headaches.

Obama also seems to have accepted that he will never have any personal leverage over Putin, while consciously ceding diplomacy with the Russian leader to Merkel. It is conceivable that the U.S. deliberately promoted the idea of arming Ukraine as a "bad cop” maneuver to allow Merkel and Hollande to go to Moscow as "good cops.”

If this has some of the obvious geopolitical downsides noted above, Washington can probably live with them. After last week’s diplomatic hurly-burly, Russia is Berlin’s problem to an even greater degree than it was before. Obama can likely live with that, too.

Sometimes leading from behind really is the best way forward.