Lisa Marie White,

Russia Insider

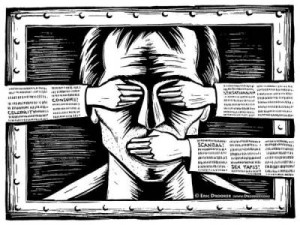

Western societies are the censorship capitals of the world, where public figures who run amok the extremely narrow confines of publicly permitted speech are required to conduct elaborate rituals of verbal self-flagellation

We hear a lot of kvetching in the Western press about censorship in Russia. The ever-amusing Josh Keating over at Slate tells us that Russian bookstores have been pulling Maus from their shelves because the graphic novel features a swastika – that dastardly Putin at it again, banning Nazi propaganda: "Before we scoff too much, it’s worth remembering that Maus has been challenged by skittish school libraries in the United States as well, but the case does illustrate something about how censorship works in contemporary Russia.”

(Before we scoff too much, American retailer JC Penny came under fire in 2013 due to a Michael Graves teapot because said teapot bore an uncanny resemblance to Adolf Hitler.)

In light of this, a recent round of ginned up "outrage” has me so puzzled and wondering if maybe we should be wondering ourselves if we are living in a censorship-free society. Pop singer Ariana Grande was filmed – without her knowledge – in a doughnut shop, licking a doughnut and then daring to disparage a tray of what I can only assume were bacon grease-filled deep-fried butter bombs with bacon-butter icing. The singer, viewing the tray, said the following: "What the f*** is that? That’s disgusting. I hate America. That’s disgusting.”

So, naturally, Americans got offended and Grande was shamed into issuing an extensive public apology and canceling scheduled appearances. Actor Rob Lowe weighed in, calling her apology "lame.” TMZ called her comments "fat-shaming.”

Here I was thinking that part of being American means you get to say "I hate America.” I thought we were Je Suis Charlie. I guess not so much.

Sergei Dorenko calls this horizontal censorship. In "The Geometry of Censorship,” Mark Ames analyzes Dorenko’s "vertical” censorship, of which he accuses the Kremlin of employing, and compares it to the "horizontal” censorship of the West:

This was contrasted to our "horizontal” censorship in the West: rather than coming from a tyrannical top-down force, our censorship is carried out horizontally, between colleagues and peers and "society”; through public pressure and peer pressure; through morality-policing; and from within oneself, one’s fears for one’s career, and fears one can’t necessarily articulate, fears that feel natural rather than imposed upon.

Under vertical censorship, you know exactly who you fear, and therefore, who and what to avoid or sneak around and oppose. But horizontal censorship feels like it comes from everyone and anyone, depriving the censored of martyrdom status.

Which makes our "horizontal” censorship in many ways more effective and powerful than the cruder Kremlin "vertical” approach to censorship—according to Dorenko’s theory.

I do not intend to take a pro-doughnut licking stance, but I do think that this incident is indicative of a distinct problem in American society. Celebrities and other public figures must issue heartfelt and repeated apologies after their remarks are made public, and are still socially and professionally shamed into retracting their comments. Unless they are Donald Trump and say things Americans secretly agree with and/or find hilarious, many times they are unable to recover their professional standing.

It may be easy to dismiss the pastry-related peccadilloes of a 22-year-old pop singer, but horizontal censorship gets carried over from the entertainment sector into political and foreign policy debates.

In Western society, horizontal censorship is tied to the offender’s self-worth. One misplaced comment or one poorly-worded Tweet, and suddenly that person’s value as a human being goes off the cliff.

Examples of social and cultural censorship in the United States are legion – from the Dixie Chicks criticizing George Bush and radio stations voluntarily pulling their music, to Seth Rogen having to apologize because he didn’t like the movie American Sniper. The example that is particularly heinous is the personal and professional attacks endured by Dr. Stephen F. Cohen over his stance on Russia and Ukraine.

Cohen, a professor emeritus at Princeton University and New York University, a former adviser to CBS News on U.S./USSR relations, and my spirit animal, has consistently dissented from the party line on Russia and Ukraine and has been rewarded for his pains with character assassination in the American media. Even the virtuous Slate got in on the action – running an article about Cohen, entitled, ‘Putin’s Pal':

As Cohen made Russia’s case and lamented the American media’s meanness to Vladimir Putin in print and airwaves, he was mocked as a "patsy” and a "dupe” everywhere from the conservative to the liberal.

Now, as the hostilities in eastern Ukraine have turned to the tragedy of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, Cohen is at it again—this time, with a long article in the current issue of The Nation indicting Kiev’s atrocities in eastern Ukraine and America’s collusion therein.

The timing is rather unfortunate for Cohen and The Nation, since the piece is also unabashedly sympathetic to the Russian-backed militants who appear responsible for the murder of 298 innocent civilians.

Never mind that Cohen has been consistently proven right. Never mind that there still is no conclusive evidence that the Eastern Ukrainian rebels are responsible for MH-17.

The shameful treatment of Dr. Cohen is particularly pernicious because, like during the lead-up to the Iraq War, it ignores a voice of peace among those clamoring for war. Only recently has the "liberal”Huffington Post seen fit to include Cohen’s viewpoint on the Ukraine crisis. Considering that U.S.-Russia relations deteriorated to their lowest point since the end of the Cold War while HuffPo jumped enthusiastically on the anti-Russian bandwagon from Sochi onward, their recent about-face appears as a weak attempt to appear unbiased.

In fact, this type of opinion-shaming isn’t limited to Western media sources. Earlier this year, I received a private message on a social network from a Ukrainian in response to post I had written in a news article’s comment section. I kept it so I can quote it here: "i hope you get ill and die in pain, you dirty russian c**t troll” (Asterisks mine.)

Censorship in the United States comes from all corners, in deleted Tweets, extensive groveling apologies, and condescending lectures on what not to say to vegetarians. In authoritarian, vertically censored societies, the devil you know has told the citizenry what speech is and is not acceptable. In horizontally censored societies, the devil you don’t know can appear at any time, to police your words, actions, and where applicable, deem you, your apology, and your value as a human being worthy of acceptance and you of forgiveness.

It sounds a lot like what Keating refers to in Slate:

We may associate censorship in authoritarian countries with jackbooted police marching into libraries to confiscate banned literature, but more often, in Russia at least, it’s self-censoring for fear of violating intentionally vague laws.

As the Times wrote recently, ascribing the reaction of Moscow theaters to a new law banning obscenity in public performances, cultural figures in Russia today describe a climate of confusion and anxiety. One publisher was quoted as saying that in Soviet times, at least we knew the rules.

If Keating’s fear-mongering has any basis in reality, then it must be a brave new world to those who remember living in the Soviet Union to finally experience Western-style horizontal censorship first-hand.

Which is worse – overzealous compliance with laws that, while admittedly vague, give citizens a guideline about what might fall under their purview – or a society that claims to be free and open but has consistently shown that it hasn’t evolved much beyond its infamous witch trials?

I think we can all agree that censorship in all forms is wrong, but I do think that we would all have one less problem without America’s puritanical exceptionalism.

_jpg/250px-ElbeDay1945_(NARA_ww2-121).jpg)