By Gilbert Doctorow and Edward Lozansky

Gilbert Doctorow is the European Coordinator of the American Committee for East West Accord, Ltd. Gilbert Doctorow is a Research Fellow of the American University in Moscow Edward Lozansky is president of the American University in Moscow, Professor of Moscow Sate and National Research Nuclear Universities

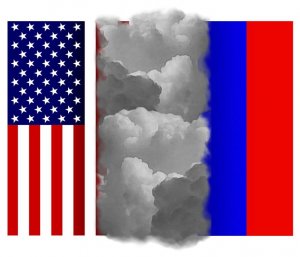

The next president should foster bilateral trust rather than suspicion

February is traditionally a time of growing optimism in Russia, as days grow noticeably longer, and snow on the ground reflects the illumination of a brighter sun across cloudless skies. Spring isn’t here, but as the month wears on there are signs that it is coming.

This year has been different with above-average temperatures, rains combined with growing economic problems, and fighting in the Middle East and in Ukraine. Continuing economic problems and a sense that the split between Russia and the United States is spiraling out of control with the Pentagon’s identification of their country as the greatest security threat to America has added to Russians’ angst.

It didn’t have to be this way. Once Moscow abandoned the dreams of conquest and control that prevailed in the Soviet era, many in both of our countries believed that Moscow and Washington would face the future together against tyrants as we did during World War II, when our two peoples fought and destroyed Nazism. Unfortunately, however, that clearly hasn’t happened.

Following Defense Secretary Ashton Carter’s statement, the United States announced a fourfold increase in budgetary allocations for manpower and materiel to be prepositioned close to Russia’s Western borders to deter what Washington perceives as further Russian aggressive designs on the Baltics and other NATO member states. The U.S. buildup is aimed at neutralizing the Russian military presence in the Black and Baltic Seas, but from the Russian perspective, these U.S. measures will pose a direct security threat to Russia itself.

These new policies were further described and justified by U.S. and NATO senior officials at the Munich Security Conference earlier this month where Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev delivered a speech further escalating the war of words between the two nations by describing the present international environment as a full-blown "Cold War.” All of this should make the Russian and American publics nervous unless both sides adopt a more civilized tone in dealing with each other.

Against this context of anxiousness and as if to actually encourage rising anti-American and anti-British feelings across Russia, the BBC in its wisdom aired a pseudo-documentary film entitled "World War Three: Inside the War Room.” In it, recently retired United Kingdom senior generals, diplomats and politicians play themselves deliberating and voting policy decisions in response to an evolving fictitious Russian hybrid attack on the Baltic state of Latvia.

To be sure, the message of "World War Three” is subject to debate. What is not debatable is that this was only the second film on this subject made by the British broadcaster. The last one was made in 1965 but was not aired for 20 years because BBC directors thought it would be too frightening for the general public. It seems now we are no longer frightened. Is this progress?

This film, intended for the British domestic audience, caught fire among Russian journalists and senior politicians, who immediately denounced the premise of a Russian attack on the Baltics as intentionally provocative, since that scenario is precisely what is used to justify the ongoing NATO buildup at Russian borders.

It is easy enough for one sitting in Washington, New York or London to dismiss the growing gloom and anti-American hysteria in Moscow, but to do so would be a serious mistake. The net result of massive mutual distrust is that no good-faith gestures or negotiations are taken at face value anymore, and every irregularity or uncontrollable event by proxies can have catastrophic consequences. Thus, Russians took almost no notice of real glimmers of hope coming out the Munich conference: the Sergey Lavrov-John Kerry statement on a cease-fire in Syria, and President Obama’s subsequent phone call to President Putin to soften the impact of the tough Pentagon rhetoric.

Campaign rhetoric is one thing and can get reckless, but as U.S. voters consider the candidates seeking their support this fall, many in both of our countries hope that whoever is sworn in as president next year will join with us to move not toward but away from the brink of disaster. The economy is important and both of our peoples are hoping for greater economic progress and growth next year, but peace and the ability of our governments to get along in an increasingly dangerous world is just as important.

_jpg/250px-ElbeDay1945_(NARA_ww2-121).jpg)