Paul R. Pillar,

in his 28 years at the Central Intelligence Agency, rose to be one of the agency’s top analysts. He is now a visiting professor at Georgetown University for security studies. (This article first appeared as a blog post at The National Interest’s Web site. Reprinted with author’s permission.)

Upset that presumptive Republican nominee Donald Trump isn’t one of them, angry neocons insist that they represent America’s reasonable foreign policy consensus, a claim challenged by ex-CIA analyst Paul R. Pillar.

The ululation among neoconservatives over their loss, at the hands of Donald Trump, of their control of the foreign policy of one of the two major American political parties continues with an op ed from one of the loudest grievers, Eliot Cohen.

Cohen enumerates many valid reasons why the vulgar and erratic presumptive Republican presidential nominee would be an awful steward of U.S. foreign policy. Along with the valid reasons to oppose Trump, Cohen also delivers a few low blows, including a comment that Trump’s "America first” slogan recalls the pre-World War II movement "that included not only traditional isolationists but also Nazi sympathizers.” One can always rely on neocons to work in a Nazi reference if at all possible.

A more fundamental deception in Cohen’s piece involves his assertion that Trump’s candidacy imperils a "two-generation-old American foreign policy consensus” that "has framed this country’s work overseas since 1950.”

It is true that there have been some depressingly persistent strains in American thinking about foreign relations in recent decades, the blatant and costly failures of which have had something to do with popular support for Trump (and, as Cohen correctly notes without acknowledging the failures, support for Bernie Sanders).

But Cohen’s overall argument is another example of neoconservatives striving to wrap themselves in a larger mantle of what Cohen calls "American global leadership” and general U.S. involvement in world affairs that is the antithesis of true isolationism. They have been able to do this partly because neoconservatism is in some respects a more muscular and militant form of some themes that can be found in broadly held American exceptionalism. But where the mantle-wrapping involves wool-pulling over eyes is that neoconservatism itself is a narrow agenda that has never reflected the kind of consensus that Cohen is claiming.

Cohen writes, "Even in this era of partisanship, there has been a large measure of agreement between the two parties, cemented by officials, experts and academics who shared a common outlook.” But especially given the recent neocon domination of the Republican Party, this simply has not been true.

A prime and recent exhibit is one of the biggest foreign policy accomplishments of the Obama administration: the agreement to limit Iran’s nuclear program, on which the partisanship has been intense (and on which Trump, by the way, is siding more with the neocons).

Or consider the biggest neocon foreign policy endeavor: the Iraq War, which a majority of Democrats in the House of Representatives, even amid all the pre-war propaganda about dictators supposedly giving weapons of mass destruction to terrorists, voted against. As for "officials, experts and academics”: the judgment of officials was never sought in a decision that was supported by no policy process, and many very credible experts and academics, including leading American foreign policy thinkers, opposed the launching of the war.

Even within the Republican Party, the neocon takeover of which came much later than Cohen’s 1950 start date for his alleged consensus, policy has been far different for most of this period than the direction that Cohen advocates. Dwight Eisenhower’s presidency was one of foreign policy restraint. Ike didn’t dive into Southeast Asia when the French were losing, he didn’t attempt rollback in Eastern Europe, and he came down hard on the British, French, and Israelis during their Suez escapade.

Richard Nixon’s foreign policy was characterized by realism, balance of power, and extraction from a major war rather than starting one. Ronald Reagan, despite the image of standing up to the Evil Empire, didn’t try to wage Cold War forever like some in his administration did. He saw the value of negotiation with adversaries, and when faced with high costs from overseas military deployments (think Lebanon in 1983-84), his response was retrenchment rather than doubling down.

George H.W. Bush had one of the most successful foreign policies of all, thanks to not trying to accomplish too much with overseas military expeditions, and to his administration being broad-thinking and forward-looking victors of the Cold War.

It wasn’t until the administration of George W. Bush that the neocons finally had their way. As for laying any claim to consensus, theirloss of support, due largely to their disastrous experiment in trying to inject democracy in foreign countries through the barrel of a gun, destroys any such claim.

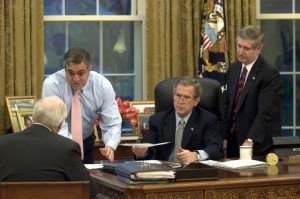

President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney receive an Oval Office briefing from CIA Director George Tenet. Also present is Chief of Staff Andy Card (on right). (White House photo)

The grand neoconservative experiment in Iraq, far from reflecting a consensus, was the product of, in Larry Wilkerson’s words, a cabal. On a more general and intellectual level, the neoconservatism which Cohen is trying to defend has also been a narrowly based political phenomenon, notwithstanding those traits it shares in kind if not in degree with broader American exceptionalism.

It is a movement with historical ties to Scoop Jackson Democrats and, farther back, Trotskyites. Along the way the movement has given us a dose of Plato, by way of Leo Strauss, and the idea that the neocons themselves know better than any of the rest of us, who can be kept in line more with myth and fable than with truth. So much for consensus.

It must be painful to lose control of the ideology of a major political party. So maybe we can feel a little sympathy for Cohen and his fellow neocons. But we should not put up with being portrayed as agreeing with them as part of a phony "consensus.”

_jpg/250px-ElbeDay1945_(NARA_ww2-121).jpg)