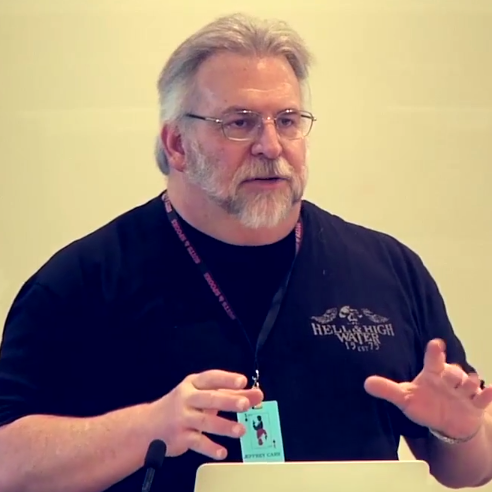

Jeffrey Carr

Cybersecurity consultant; author, “Inside Cyber Warfare” ; Founder, Suits and Spooks; Articles reflect the author’s personal views, not his employers or clients

On October 7th, the U.S. government formally accused the Russian government of interfering with the U.S. election process.

The U.S. Intelligence Community (USIC) is confident that the Russian Government directed the recent compromises of e-mails from US persons and institutions, including from US political organizations. The recent disclosures of alleged hacked e-mails on sites like DCLeaks.com and WikiLeaks and by the Guccifer 2.0 online persona are consistent with the methods and motivations of Russian-directed efforts. These thefts and disclosures are intended to interfere with the US election process. Such activity is not new to Moscow — the Russians have used similar tactics and techniques across Europe and Eurasia, for example, to influence public opinion there. We believe, based on the scope and sensitivity of these efforts, that only Russia’s senior-most officials could have authorized these activities.

On October 14th, NBC News reported that the CIA is planning a cyber attack against Russia, and that the target is Russian President Vladimir Putin and other Russian leaders.

On October 15th, Russian Presidential Aide Yury Ushakov said in response to that news — "We will react, of course, especially given specific figures from the Russian government were mentioned.”

From the U.S. government’s perspective, it is the victim of Russian aggression; that the evidence pointing to the Russian government is sufficient to meet the attribution standard of "reasonable certainty”[1], and so it is entitled to respond in self defense as long as its response is proportionate to the attack[2].

What If?

It’s certainly possible that Putin directed the FSB and GRU at different times (one in 2015 and one in 2016) to mount a secret influence operation that would favor Donald Trump’s run for President, and that those normally competent spy agencies executed this secret operation by using not one but two blown threat actor groups (Fancy Bear and Cozy Bear), Russian servers and tool sets, free Russian-hosted email accounts on Yandex, and distributed the files via Wikileaks (a long suspected Russian front). Oh, and also create a FancyBear[.]net website and a character named Guccifer 2.0 who negotiateswith reporters and speaks at security conferences. Because, you know, SECRET.

Or, it’s possible that the Russian government hasn’t directed this attack, and that the White House, in the midst of the ugliest election season in our lifetime, fueled with Russophobic hysteria generated in part by headline-grabbing cyber intelligence firms, has mis-attributed it to a State actor and is now about to launch a cyber attack against a nuclear power w/ cyber capabilities close to our own.

What then?

Under international law, Russia could pursue remedies at the U.N. Security Council and the International Court of Justice, or it could respond with countermeasures proportionate to whatever action the U.S. takes.

No one knows what Russia’s actual cyber capabilities are, but based upon the quality of their scientific universities and the world-wide respect garnered by their computer science engineers, they certainly are superior to the Keystone Cops antics of Fancy Bear, Cozy Bear, and Guccifer 2.0.

We already have enough real problems with Russia in Syria and Ukraine. Someone, maybe Russian, has embarrassed the Democrats but there’s no hard proof as to who’s responsible. And the bottom line is that the DNC bears at least some of that responsibility no matter who attacked them.

This decision by the White House to name the Russian government in the DNC hack and threaten them with a response is both inflammatory and irresponsible; especially when our entire U.S. network infrastructure is so vulnerable to retaliation by cyber means.

NOTES:

[1] Kenneth P. Yeager v. The Islamic Republic of Iran, Iran-U.S. C.T.R., vol. 17 , p. 92, at pp. 101–102 (1987) — "in order to attribute an act to the State, it is necessary to identify with reasonable certainty the actors and their association with the State.”

[2] Jensen, Eric Talbot, Cyber Attacks: Proportionality and Precautions in Attack (October 1, 2012). 89 Int’l L. Stud. 198 (2013). Available at SSRN:https://ssrn.com/abstract=2154938 orhttps://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2154938

_jpg/250px-ElbeDay1945_(NARA_ww2-121).jpg)