Published 28-11-2012, 01:23

On 16th November the lower house

of the US Congress voted overwhelmingly in favour of adopting the so-called

Magnitsky Bill. Since the passage of this bill is linked with the repeal of the

Jackson-Vanik amendment, which will finally normalize US-Russia trade

relations, a reluctant President Obama has no choice but to sign it into law.

With Moscow already promising retaliation, US-Russia relations are clearly

headed for fresh turbulence.

On 16th November the lower house

of the US Congress voted overwhelmingly in favour of adopting the so-called

Magnitsky Bill. Since the passage of this bill is linked with the repeal of the

Jackson-Vanik amendment, which will finally normalize US-Russia trade

relations, a reluctant President Obama has no choice but to sign it into law.

With Moscow already promising retaliation, US-Russia relations are clearly

headed for fresh turbulence.

Given the precarious state of the US economy, the turmoil in the Middle East, the persistent menace of terrorism and the relentless rise of China, it seems odd that Congress was able to find the time to pass legislation which is focused on the internal affairs of Russia and, which, moreover, risks further destabilizing the international system. It is even odder that US legislators, normally averse to effective consensus on vital domestic issues, have nevertheless demonstrated strong bipartisanship on the Magnitsky Act (it passed with a majority of 365 to 43). Indeed, as Edward Lozansky of the American University in Moscow has pointed out, we are witnessing a unique situation in which both sides of the US political spectrum, as well as most media, consistently maintain a strong anti-Russian stance and consider Putin’s regime virtually as evil as that of the Soviet Union. Such unity was rare even during the Cold War.

Why the US is behaving in this way cannot be satisfactorily explained by the standard analytical tools of geopolitics. Rather, we need to reach for the toolbox of psychology. America’s political class understands that the "sole superpower” and its Western allies are in relative decline, having brought upon themselves an intractable economic and moral crisis. It also understands that, with the rise of China and the other BRICs, the end of incontestable Western domination looms ever closer. In the face of this development, the mere presence of a doggedly sovereign "Putin’s Russia” is seen as an unacceptable affront. Moreover, not only does Moscow dare to flaunt its independence; it also entertains big geopolitical ambitions by aiming to restore (without Western "permission”) its historical influence in strategically important Central Asia.

The Magnitsky Bill is not about democracy and human rights; if it were, how could the US political class be comfortable with such medieval-like outrages in its own camp as Saudi Arabia’s persecution of women whose only "crime” is campaigning for the right to drive cars? Above all, it is about the following three things:

• America’s inability to come to terms with the limits of its power;

• Its failure to grasp that a functioning democratic system can evolve from the ashes of totalitarianism without being "implanted” there by the West and without Western supervision;

• And its reluctance to strike a strategic partnership with a resurgent Eurasian superpower on the basis of genuine equality, mutual respect and due regard for each other’s interests.

Today we are witnessing the emergence of increasingly prosperous and democratic superpowers (countries that are deemed by the West to have "lost” the Cold War) which do not need and which, in fact, reject, US "guidance” and security guarantees. Welcome to the new world for which America is not yet equipped and in which it is still struggling to find its place.

Questions:

• Russia will surely retaliate following the passage of the Magnitsky Bill, thereby further escalating the tensions. Is this to be condoned?

• Would Moscow demonstrate genuine wisdom and statesmanship by showing an understanding for America’s predicament and refraining from retaliation?

------------------------

The topic for the Discussion Panel is provided by Vlad Sobell, Expert Discussion Panel Editor (New York University, Prague)

------------------------

Expert Panel Contributions

Statement opposing HR 6156, the Russia and Moldova Jackson-Vanik Repeal and Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012

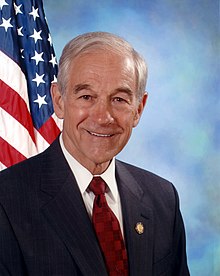

Ron Paul

Ron PaulCongressman, R-TX

16 November 2012

Mr. Speaker I rise to strongly oppose this legislation. Unfortunately, Congress has ruined an opportunity to overturn an anachronistic impediment to free trade with Russia by attaching to it an interventionist and provocative "human rights" bill that will worsen US-Russia relations.

With Russia's recent accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) Congress is obligated to repeal the "Jackson-Vanik Amendment," a 1974 era piece of legislation that sought to condition normal trade relations with the Soviet Union (which no longer exists) upon liberalization of emigration rules for Soviet Jews. WTO members are obliged to eliminate trade barriers with other members. So the repeal and extension of normal trade relations simply should have been a formality. Unfortunately Congress instead took this as an opportunity to meddle in the internal affairs of Russia, which will worsen US-Russian relations and have a negative economic impact on the United States.

By attaching the so-called "Magnitsky" bill to the Jackson-Vanik repeal, Congress will direct the State Department to draw up a list of Russians it believes are responsible for human rights abuses. These people will be denied entry into the United States and have their assets seized by the US government. The implications of this reckless move are stunning.

What is even more dangerous is that the bill directs the US government to also consider "evidence" provided by international non-governmental organizations when it determines who should be sanctioned by the US government. Non-governmental organizations are not legal tribunals, and in fact many are politically-motivated pressure groups. Many are funded by governments or political parties and in exchange do their bidding. This ironically reminds one of the "people's tribunals" set up under the Soviet system, where evidence was considered irrelevant.

These sanctions in this bill against individuals are the economic equivalent of President Obama's "kill list." Individuals will be placed on this list under dubious and ill-defined criteria, without due process or sound evidentiary requirements.

If this bill becomes law, we should expect a response from Russia and perhaps other of our trading partners – particularly as many of our colleagues have suggested that the Magnitsky Bill should serve as a model for our relations with the rest of the world.

We might imagine the Russians or the Chinese passing similar legislation, banning Americans from entry and seizing the assets of Americans allegedly involved in "human rights violations." What if they considered the US bombing of Libya, which resulted in the death of thousands of civilians from NATO bombs, such a violation?

If Congress really is concerned about the human rights of prisoners, perhaps they might take a look at the terrible treatment of US Army Private Bradley Manning while incarcerated and awaiting trial. Last year Amnesty International wrote to then-Defense Secretary Robert Gates that Manning's "inhumane" treatment while in custody "undermines the United States' commitment to the principle of the presumption of innocence." Congress remains silent.

In reality, this bill is about politics more than human rights. Listening to the debate it is obvious that many supporters of this legislation simply do not like the democratic choices that the Russian people made in recent elections. Therefore they do what they can to undermine the Russian government and encourage "regime change." Again, how would we react?

I encourage my colleagues to join me in opposing this legislation in its current form and to push for a bill that simply extends normal trade relations with Russia without meddling or provoking. When it comes to human rights, the United States should most definitely lead the world by its own example. On that measure, we still have a lot of work to do.

Edward Lozansky

President American University in Moscow

Professor of World Politics, Moscow State University

The Magnitsky Bill is unique in that never before has a foreign national who gave up his US citizenship and is under investigation for tax evasion in Russia been able practically single-handedly to successfully lobby both chambers of Congress to stir up US-Russia confrontation at a time when the two countries urgently need to cooperate to meet global security and economic challenges.

I am referring, of course, to William Browder, head of the Hermitage hedge fund who came to Russia in April 1996 with $25 million borrowed from the late banker Edmond Safra and quickly turned it into $4.1 billion or 2,549 percent return (!) by betting on stocks and, as Russian courts allege, through some complicated tax-evasion schemes.

The Hermitage founder Edmond Safra would have been proud of his partner hadn't he been burned alive in a very suspicious fire in a Monte Carlo hotel which probably has more security personnel than maids.

More on Safra and his National Republic Bank of New York can be found in Robert Friedman's article in the New York Time Magazine. The information about the banker supplied there is hardly complimentary. It includes a startling account of regular deliveries of crisp new $100.00 bills flown five nights a week by the planeload from JFK nonstop to Moscow, where the money became, we are told, part of a money-laundering operation of mind-boggling proportions by the Russian mob and a vast international crime syndicate. According to this article, one of the principal instruments in this operation was the above-mentioned National Republic Bank of New York.

Let's make things absolutely clear. Corrupt officials from any country should be punished. Just as the House members voted last week, they should be denied US entry and their illicitly gained hidden assets frozen. However, as stated many times by White House officials, no additional Congressional bill is needed since the US executive branch of government already has laws at its disposal for both purposes.

So the Magnitsky Bill is not about democracy, human rights or fighting corruption. It was necessary because the majority of House Members on either side of the aisle could not find enough commonsense to graduate Russia from the obsolete Jackson-Vanik Amendment for US businesses to be able to take full advantage of Russia's accession to WTO. The graduation should, of course, have been done more than 20 years ago, when newly born Russia, free from the stigma of communism, lifted all Soviet-era restrictions on emigration.

However, that was seen to be too much of a gift to Moscow. The Magnitsky Act thus came in very handy to those whose minds are set in the Cold War mold, who are simply incapable of letting Cold War tools and practices go.

This bill undermines the fundamental presumption of innocence principle, punishing individuals who have not been charged by any court, let alone stood trial. Its House version proposes to apply selective rather than universal justice by mentioning only Russian corrupt officials but not those of other countries. The Senate version has the universal justice language but the senators are under intense pressure from lobbyists and the US media to "drop this nonsense" and vote for the House version, the sooner the better.

As the recent presidential candidate Ron Paul (R-TX) says, this bill is "dangerous" since it "directs the US government to also consider ‘evidence’ provided by international non-governmental organizations when it determines who should be sanctioned by the US government. Non-governmental organizations are not legal tribunals, and in fact many are politically-motivated pressure groups. Many are funded by governments or political parties and in exchange do their bidding. This ironically reminds one of the ‘people's tribunals’ set up under the Soviet system, where evidence was considered irrelevant".

In the coming days it will be interesting to see if the senators yield to this unceremonious lobbyist pressure and whether the Russian side, as Vlad Sobell suggests, demonstrates greater statesmanship by taking the high road and defusing this confrontation for good.

A speedy conclusion of the investigation into the causes of Magnitsky's death and into related corruption cases involving the Hermitage Fund are also clearly in order.

William Dunkerley

Publishing Consultant

I would be very surprised if either Russia or the United States were to demonstrate any genuine wisdom or statesmanship regarding the Magnitsky issue. The problem is that neither side seems to understand the underlying motivation behind the initiative. The Russian administration perceives it as an American intrusion into a domestic matter. The American Congress couches it as an earnest attempt to promote improved human rights in Russia. A minority segment of the Russian population actually agrees with that view.

What both sides should understand is the established fact that the Magnitsky Bill is part of an international effort to show Russia in an unfavorable light, and perhaps even delegitimize its leaders. When the bill was introduced in the House of Representatives, the presenter added, "I would also like to underscore that this effort is far from just a US initiative. Similar legislation is being considered in nearly a dozen other legislatures around the world." I don't know who is behind that international coordination. But, the European Union and the Canadian Parliament have already enacted measures similar to the American Magnitsky Bill. Those legislators, along with their American counterparts seem to have been duped by foreign agitators whose aims these initiatives appear intended to serve.

Little attention has been focused on this aspect of the issue. The story told by the mainstream media about the Magnitsky legislation skirts it entirely. It reminds me of how the media handled the Alexander Litvinenko death case. News reports had quoted a deathbed statement by Litvinenko that fingered Russian president Vladimir Putin. The only trouble is that the whole murder story was a fabrication by an arch enemy of Putin's seeking to discredit him. I wrote a book titled The Phony Litvinenko Murder. In it I show that Litvinenko was not a spy, and he never worked for the KGB. The London coroner never deemed his death to be a homicide. The deathbed statement turned out to be a fake.

There's been scant coverage about all that in the press. The fabricated story got the news coverage, not the underlying motivation behind the fabrication. Recently, the case that the British government had advanced against the Russian administration over Litvinenko began to unravel. That's not been covered either. Even news sources that specialize in providing objective news about Russia have strangely refused to cover the startling turnabout. That leaves news consumers with only the fabricated stories that denigrate Russia. In that respect, these so-called objective sources are playing into the hands of those who advance the phony stories.

The same is true in the Magnitsky matter. If there is no coverage given to the underlying motivation and the international coordination, then the issue will never be seen for what it really is. And that creates a knowledge vacuum. That atmosphere will only invite Russia and the United States to bicker with an absence of genuine wisdom and statesmanship.

Alexander Rahr

Research Director, German-Russian Forum, Berlin

It seems not to have been a coincidence that at the same time as the US Congress passed the Magnitsky Bill, the German Bundestag also endorsed a harsh resolution criticizing Russia for her departure from democracy. Indeed, there are so many serious challenges confronting Germany and the EU these days – not least the crisis of the Euro zone and a new war in the Middle East – that neutral observers cannot but wonder why this focus on Russia?

The answer may be simple. The West fears that its liberal model is not the "End of History", as generally thought in the 1990s. The global agenda will witness growing competition between the Transatlantic liberal value system and the Asian state capitalist model, which is more authoritarian. It is an open question as to which of the two systems will be better equipped in struggling with the emerging global challenges of the 21st century. Russia is the first European country that has firmly stated that it rejects a Western liberal model for its political and socio-economic development.

Moreover, Moscow is beginning to forge a coalition of the strongest developing economies - the BRICs - against the West. The economic growth in the BRICs states is double that of the US and EU, a situation that will persist in the upcoming years, much to the discomfort of the West. When China's economy overtakes America’s in a decade or two, the world’s economic order might shift its orientation from WTO rules written and enshrined by the Transatlantic community toward other centers of power. While China and India keep quiet and silently develop their economies, President Putin continues to engage in a rhetoric that welcomes the new multipolar world order. That makes him and Russia the main target for Western criticism. Having said all that, I don't want to sound like someone who clearly sympathizes with the new – less European, more Asian – world order. The world may become much less liberal. But the question is: can we stop the world moving along this path by force? The answer clearly is "no”.

Alexandre Strokanov,

Alexandre Strokanov,Professor of History,

Chair of Social Science Department,

Director of Institute of Russian Language, History and Culture,

Lyndon State College,

Lyndonville, Vermont

Of course, the Magnitsky Bill is not about democracy and human rights. Many American congressmen agree with this, including Representative Ron Paul who said at the debates in the United States House: " (i)n reality, this bill is about politics more than human rights. Listening to the debate, it is obvious that many supporters of this legislation simply do not like the democratic choices that the Russian people made in recent elections.” So, what should the Russian government do?

Certainly, they may simply ignore the bill and follow the old proverb "the dogs may bark; the caravan goes on!” An argument in favor of this approach will be that this bill is unlikely to hurt Russian national interests significantly, and it is just a political "flash mob” in the United States Congress. Indeed, the only real danger here is if the bill’s actions will be spread on the assets of Russian corporations that have business ties with American partners, and for that purpose, keep their money in American banks. However, it will just further jeopardize Russian-American economic ties and backfire against American economy. Meanwhile, remembering how irrational the American political class may be, such an option should not be ruled out completely.

Since it is quite obvious that the major point of this bill is political, the response of the Russian side could be also mainly political. The bill in reality may become just a "dead paper,” since it depends on the position of the American executive branch how it is going to be implemented. Consequently, the response of the Russian side should depend not so much on the rhetoric in the Congress, but on real actions of the Obama and following administrations.

Of course, few American bureaucrats keep their money in Russian banks, and to punish honest American entrepreneurs with similar threat will be very unwise. The recommendation of the Russian legislature should be dealing with a different dimension, rather than individual assets of Americans in Russia. What will be significantly more sensitive for any United States Administration, in present time and foreseeable future, will be the issue of the national debt. That is why the bill that is going to be passed by the Russian legislature could issue a recommendation to the President and Government to link implementation of the Magnitsky Bill with question about acquisition and possession of the United States Treasury Securities. In September, 2012, Russia held 162.8 billion dollars in the US Treasury Securities, which is 2.5 times larger share than, for example, Germany. Many people in Russia already are questioning the wisdom of keeping their country’s savings in such form. That is why bringing this topic to the

floor of the Russian State Duma may find support among general public in the country. It would be met with understanding in many American political circles, which oppose the overspending of the Obama administration and pushing the country deeper into a debt hole.

Finally, Russian Americans and everybody in the United States who want relations between these two great countries to develop successfully need to join their efforts and to make their voices heard by our politicians. While the Magnitsky Bill was still debated on the floor of the United States House, I emailed our Vermont Representative Peter Welch and encouraged him to follow Ron Paul and vote against the bill. However, I never heard back from him, and I know that he voted "Yea” to the bill. It is easy for Russophobes and the Cold War warriors to ignore a single voice, but it will be more difficult if it becomes the voice of hundreds of thousands voters who wish for the United States and Russia to be friends and partners, rather than geopolitical enemies or rivals.

Professor Nicolai N. Petro

Department of Political Science

University of Rhode Island

As I see it, the passage of the Magnitsky Bill has nothing to do with human rights or Russia. It is a manifestation of Congressional politics, in all its naked glory.

The bill's strong bipartisan support results from it being as close to a "perfect bill" as one can get out the US Congress these days. It is politically perfect because it gives Congress moral standing at no apparent cost, while shifting the burden of implementation elsewhere.

First, it does absolutely nothing to punish human rights violators in Russia, while giving the appearance of doing so. Any Russian official foolish enough to still have assets in the United States will have at least half a year to transfer them, while those who wanted to visit Disneyland with their kids (yes, they too share guilt under the House version of this bill), will now have to settle for Disneyland Paris.

Second, while ostensibly targeting those responsible for violating human rights, it shifts the actual responsibility for identifying them to the State Department, on the basis of "credible information.” Since the State Department does not have staff to engage in this sort of inquisition, and already relies on human rights organizations to do so, this completes the privatization of the human rights aspect of U.S. foreign policy, which apparently suits everyone in Washington just fine.

In the future, we should expect human rights NGOs to apply for more funding, so that they can fulfil this congressional mandate. Individual congressmen to get the publicity they crave, by holding hearings at which they can, alternately, chastise human rights groups for not identifying enough human rights abusers, or castigate the White House for being too cosy with them. Meanwhile, and most importantly, responsibility for implementing the law will fall to the White House (perhaps along with State), neither of which has any incentive to act on the list, since it is nothing but a headache for implementing the broader U.S. foreign policy agenda.

Thus, while as Congress congratulates itself on having "stood up" to Russia, this administration (and future administrations) will quietly waive its application for national security reasons.

And that, children, is how a bill becomes a law.

Mark Nuckols

Mark NuckolsProfessor of law and business at Moscow State University and at the Russian Academy of National Economy

This article was originally published by Moscow Times on 26th November

Sergei Magnitsky was a Russian lawyer who exposed the fraudulent use of corporate documents of his client to defraud both his client and the Federal Treasury of $230 million. Rather than arrest and prosecute the persons Magnitsky testified were responsible for this crime, prosecutors had Magnitsky himself arrested and imprisoned. After enduring 11 months of inhumane treatment, Magnitsky died in police custody under suspicious circumstances. His death is a tragedy and miscarriage of justice and demands a thorough investigation by the Russian government. Unfortunately, however, the wheels of justice in Russia often fail to turn as they should, particularly when they threaten wrongdoers in the government.

The U.S. Congress has responded with the Magnitsky Act. The proposed law would require the U.S. Secretary of State to provide Congress with a list of people believed complicit in Magnitsky’s death, to deny them visas to the U.S. and to direct U.S. banks to freeze any assets they hold in the country. If U.S. President Barack Obama signs this law, it will be a mistake. It would violate basic principles of the rule of law, needlessly poison U.S. relations with Russia, and fail to advance the cause its authors believe they are championing. Obama should veto this bill if it passes Congress.

One disturbing feature of this bill is its extraordinary selectivity. Magnitsky’s arrest, prosecution and death in police custody are hardly unique in Russia. The only reason congressmen even heard of Magnitsky was because of his client: Hermitage Capital, a prominent and wealthy hedge fund manager that heavily lobbied U.S. and European lawmakers to propose the Magnitsky Act. The U.S. Congress has conspicuously not shown the same concern for human rights violations in dozens of other countries, namely China, with whom the U.S. trades extensively. It is true that the U.S. Senate has approved an alternative version of the proposed law that extends its application to "human rights violators” in all countries worldwide, but in both versions Russia remains the clear target of the law

The main reason the U.S. Magnitsky Act is a bad idea is that the Magnitsky affair is strictly an internal matter for Russia. The events that led to Magnitsky’s death occurred on the territory of an independent state with its own judicial organs, whose sovereignty the U.S. should respect.

This Magnitsky Act’s blacklist is a symbolic judgment of guilt — not only of the accused officials but of Russia itself. It is not a verdict rendered by a competent judicial body after a proper trial and opportunity for the accused to defend themselves but a politically loaded statement by the U.S. Congress aimed at Russia. If these officials are in fact guilty of violating Russian law, only a Russian court has the jurisdiction and competence to make this determination. If Russian courts fail to provide justice in this case, it is a failure that must be addressed by Magnitsky’s fellow citizens, not U.S. lawmakers, the State Department or Obama.

To be sure, the sanctions that the act levies out are purely symbolic. If the accused officials are, in fact, guilty of an extra-judicial murder and embezzlement, being denied permission to visit Disneyland or Las Vegas is a parody of just and appropriate punishment. It is safe to assume that these officials moved their money and assets out of the U.S. long ago if they were ever there to begin with. The more serious concern for Russian officials is that European countries will adopt similar and perhaps broader legislation.

But enactment of the act will have other serious, if unintended, consequences. Although the U.S. and Russia are not strong allies, they do have many vital common interests, ranging from trade and international security to nuclear arms control and fighting global terrorism. Passage of the act will inevitably cause unnecessary friction between Washington and Moscow.

Russians are proud people — perhaps too proud at times — but perceived hectoring from the U.S. about Russia’s failings is far more likely to provoke indignation and anger than renewed resolve to root out corruption and injustice in Russia’s bureaucracy and criminal justice system.

The death of Magnitsky is a tragedy that demands justice, and he deserves a fitting tribute for his sacrifice and his devotion to the rule of law. But the Magnitsky Act achieves neither of these objectives.

Patrick Armstrong

Patrick Armstrong Analysis,

Why this bizarre American obsession about Russia – a power that truly is not very pertinent to Washington’s strategic and security concerns? Considering, for example, what Obama and Romney talked about in their foreign policy debate, we see that Moscow hardly featured. I’m perplexed and all I can offer in explanation is a jumble of partly-baked theories.

Perhaps lefties dislike Russia because it rejected socialism; indeed the Soviet experience stands as an indictment against the whole scheme. If you believe more government is the solution, or that equality is the answer, Russia’s rejection of the Soviet experiment is a standing rebuke to your convictions.

Righties dislike Russia because, communist or not (and how many think it still is?) it’s still Russia. But why should they dislike Russia per se? Apart from the communist period, Russia has never been very germane to American concerns – not, at least, since the Alaska Purchase. And yet, as David Foglesong has argued, many Americans were obsessed about Russia long before the Bolsheviks. Russia was then seen as a sort of backwards twin brother. But Americans had a long obsession with China too: all the missionaries, the "who lost China” excitement in the 1950s. Why Russia still?

Another notion is that Americans have to have a rival, an opponent, a counter, an enemy even. It’s geopolitical chiaroscuro: the light can only shine against the darkness. Russia is large, significant and gives a contrast more substantial than, say, Venezuela would. But, best of all, unlike China, US-Russia trade is pretty inconsequential. So Russia is a low-cost opponent. It’s safe to abuse Russia; abusing China comes with a cost.

In periodic American fits of moral censure, Russia is a safe target. An issue as trivial as Pussy Riot can be played up as a momentous moral outrage. On the other hand, any sustained condemnation of the treatment in Saudi Arabia of Shiites or Pakistani and Filipino servants would come with a cost. Outrage against Russian "occupation” of parts of Georgia is one thing; outrage about Chinese occupation of Tibet would be something else. It is always pleasing to illustrate one’s moral superiority by manifesting outrage against someone else’s moral imperfections but a target that can bite back would cost more than the transitory satisfaction of being among the Saved Remnant. Russia’s sins are a perfect fit: pleasing moral superiority without uncomfortable consequences.

Or is Russia an ungrateful child? In the 1990s there was much talk about US aid and advice reforming Russia, the "End of History” and all that. Russia was, evidently, on the edge of becoming "just like us”. But it didn’t and such back-sliding cannot be forgiven.

Or is Russia just one of those unfortunate countries whose fate it is to be explained by foreigners after a two-week visit? A palimpsest on which to write the presumptions you brought? Martin Malia wrote a fascinating book showing how Westerners from Voltaire onwards found Russia to be the perfect exemplar of whatever it was that they wished it to be. So, in Russia you can find whatever you’re looking for: a "geostrategic foe”, for example.

So abusing Russia satisfies many needs: a safe opponent; a contrast that can be painted as dark as you like; an object of feel-good moral righteousness; a sullen teenager who won’t listen to Daddy; a blank slate on which to write.

But best of all, something like the "Magnitskiy Bill” feels good and it doesn’t cost anything much. The geopolitical equivalent of banning Big Gulps in New York City.

Sergei Roy

Former Editor-in-Chief, Moscow News

I welcome the Magnitsky Bill with all my heart. Certain Russian bureaucrats will not be allowed into the United States? That's just great, and the longer the list, the better. Those officials will squander away less public money during their "business trips," on which they have this uxorious habit of taking along and entertaining their wives/mistresses. I would extend the Bill to cover not only the bureaucrats themselves but their wives, sisters, mothers-in-law, and especially ladyloves, who will no longer be able to go on shopping sprees, not in the US, at any rate. Their offspring, too: I'd bar their entry into US educational establishments. Let their parents endow Russian institutions of learning, instead of sponsoring US ones.

The US will not permit various Russian officials to stow away their ill-gained assets (stolen goods, in fact) in US banks? That's really marvelous news. I would only extend this measure to all foreign banks in which US financial institutions have even minimal control, especially in Europe. There would remain, of course, shady offshore nooks in which to salt away money pilfered from Russia, but these could be dealt with by RF legislation if/when a truly patriotic government is in place here.

The really important fact is that that bill leaves 99.99 percent, or more, of Russia's population totally unconcerned and indifferent, except perhaps for muttering disgustedly, if they hear of it at all: "Ah, those Americans. Breaking wind as usual. Spoiling the air. We should worry!" If the bill punishes anyone at all, it is the class of corrupt bureaucrats, the very people who, like the true compradors that they are, need the West most and are the West's most reliable agents of influence.

Of course, the Magnitsky Bill is a fine propaganda ploy and a handy tool to further zombify the US population, inculcating in it fear and hatred for that bogeyman Russia. There does not seem to be anything much that Russia can do to counteract this idiocy.

Politically this zombification results in Americans approving of, or electing officials who initiate and implement, costly measures like BMD and other symbols of America's imperial grandeur. On this score, though, Russia can do something diplomatically, militarily and even, believe it or not, financially.

RF Foreign Ministry is talking of tough retaliatory measures. Well, if these measures are in any way symmetrical (which seems to be the prevailing diplomatic fashion), they will result in a few US individuals not getting Russian visas. That's less than a storm in a teacup. Sergei Lavrov and Hillary Clinton will have abrasive things to say to each other when they meet, or M-me Clinton will walk out during Lavrov's speech, and that will be news, only there will be nothing new about that news. Diplomatic fun and games, that's all.

Finances is where it really hurts the US, and here Russia could do something effective to show that indulgence in Russophobia can be costly. In this sense the Magnitsky Bill is a godsend. It can be used as a pretext for imposing stricter controls on the circulation of dollars in Russia and generally moving away from the dollar sphere. Dollars still change hands in Russia, though officially no shops or services are permitted to accept them. They certainly change hands in corrupt schemes or outright thieving - just look at those safety deposit boxes crammed with millions of dollars stolen by the highly placed female crooks at the Defense Ministry. Introducing harsher penalties for these transactions will not of course root them out completely, but it would be a step in the right direction.

Even to one who is in no way conversant with financial affairs of any scope it looks not impossible that effective measures could be taken to squeeze the dollar, especially in its cash form, out of Russia. The most telling measure would of course be a switch from pricing oil and gas in dollars to roubles, at least in the sphere of Russia's immediate influence, to start with.

The trouble is, however, that measures of this sort could only be taken by Russian officialdom, a class that appears to consist mostly, if not entirely, of ardent worshippers of the Almighty Dollar. The very people, in fact, whom US Congress so stupidly punishes. They might show their patriotic mettle by doing things along the lines indicated here. Only they won't.

Author’s Note:

Please do not take what I have to say about the Magnitsky Bill for a hoax or an attempt to sound cute, original or outrageous à la Zhirinovsky. What is posted here is quite sincere; it logically follows from my considered view of the state of affairs in Russia.

_jpg/250px-ElbeDay1945_(NARA_ww2-121).jpg)