The mass media in the United States and

Russia/the Soviet Union have been central to the problems in relations between

the two countries for a long time. But journalists and other commentators on

contemporary American-Russian relations also could play important roles in reducing

tensions and overcoming negative stereotypes.

The mass media in the United States and

Russia/the Soviet Union have been central to the problems in relations between

the two countries for a long time. But journalists and other commentators on

contemporary American-Russian relations also could play important roles in reducing

tensions and overcoming negative stereotypes.

The mass media in the United States and Russia/the Soviet Union have been central to the problems in relations between the two countries for a long time. But journalists and other commentators on contemporary American-Russian relations also could play important roles in reducing tensions and overcoming negative stereotypes.

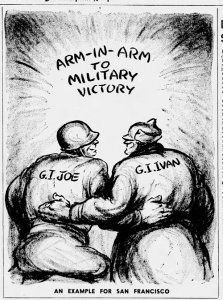

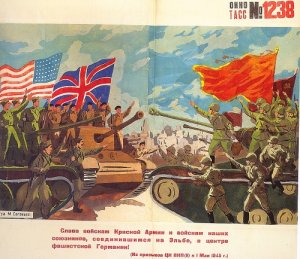

When American and Soviet soldiers embraced at the Elbe River in April 1945, reporters, editors, and cartoonists in both the United States and the Soviet Union hailed the meeting as a symbol of the potential for postwar cooperation between the two peace-loving countries. "Red Ivan, G.I. Joe Are Brothers Under the Skin,” read one headline in St. Louis. A Louisville cartoonist drew a Soviet arm and an American arm clasping hands in a "V” for victory. A Soviet artist celebrated the joyful meeting of troops from both sides of the river in a poster distributed by TASS.

When American and Soviet soldiers embraced at the Elbe River in April 1945, reporters, editors, and cartoonists in both the United States and the Soviet Union hailed the meeting as a symbol of the potential for postwar cooperation between the two peace-loving countries. "Red Ivan, G.I. Joe Are Brothers Under the Skin,” read one headline in St. Louis. A Louisville cartoonist drew a Soviet arm and an American arm clasping hands in a "V” for victory. A Soviet artist celebrated the joyful meeting of troops from both sides of the river in a poster distributed by TASS.

Those hopeful feelings and positive images in the spring of 1945 did not simply slip away in an inevitable deterioration of relations between the USA and the USSR. Instead, starting in the summer of 1945, anticommunist publishers and journalists in the United States deliberately fomented hostility to the USSR, which they alleged was akin to Nazi Germany rather than a friend of America. Soviet leaders and propagandists deeply resented and fiercely criticized the campaign of denunciation. American journalists then decried the Soviet war of words against the United States, which they claimed was central to the newly named "Cold War.”

Those hopeful feelings and positive images in the spring of 1945 did not simply slip away in an inevitable deterioration of relations between the USA and the USSR. Instead, starting in the summer of 1945, anticommunist publishers and journalists in the United States deliberately fomented hostility to the USSR, which they alleged was akin to Nazi Germany rather than a friend of America. Soviet leaders and propagandists deeply resented and fiercely criticized the campaign of denunciation. American journalists then decried the Soviet war of words against the United States, which they claimed was central to the newly named "Cold War.”

Although mutual demonization was at the heart of the long Cold War conflict, journalists sometimes played more constructive roles and promoted mutual understanding instead of antipathy. One example is especially noteworthy. In October 1982 – when tension between the Reagan administration and the Soviet government was near its peak

Soviet correspondents from Pravda, Izvestiia, and other papers met with editors of newspapers in New England at Colby-Sawyer College in New Hampshire. At the start of the two-day conference, American editors feared that they would face propagandistic diatribes by the Soviet correspondents. The tenor of their briefings also led one editor to complain that the Americans seemed "to be gearing up for some adversarial confrontation.” But by the final session the American and Soviet journalists were discussing how to exchange articles between their publications, how to maintain their personal contacts, and how to urge reduction of travel restrictions for correspondents in both countries. Some of the Soviet journalists then stayed at the homes of American editors and took a tour of the offices of the Boston Globe. As a result of the close encounters, negative stereotypes were shattered and the journalists resolved to work toward improved relations between their countries. By 1988 the mutual demonization of the Cold War was ending – in part because of a widespread series of citizen exchanges like the October 1982 meetings.

The degeneration of relations between the United States and Russia in the twenty-first century has been spurred to a significant extent by mass media distortion and exaggeration. As the dialogue between American and Soviet journalists in 1982 suggests, though, the editors and correspondents of the two countries are not doomed to eternal hostility. They could choose, instead, to focus on the need for cooperation between America and Russia – against infectious diseases, the proliferation of nuclear weapons, the arms race, terrorism, and other problems.

_jpg/250px-ElbeDay1945_(NARA_ww2-121).jpg)