Daniel McCarthy

Daniel McCarthy is editor at large of The American Conservative.

The former acting attorney general’s testimony didn’t include anything new.

Sally Yates didn’t reveal much that was new in her testimony to a Senate Judiciary subcommittee. But she has arguably invented an entirely new genre of political spectacle: the news remix. Taking elements already well known to the public—Michael Flynn’s inappropriate dealings with the Russians, his resignation after weeks of speculation—Yates added a personal touch of drama and defiance, and the result was a fresh spate of headlines.

It certainly was not news that Yates, then in her capacity as acting attorney general, had complained to the Trump administration about Flynn back in January. Press secretary Sean Spicer noted on February 14 that Yates had spoken to White House counsel Don McGahn the previous month and, in Spicer’s words, "She said, we wanted to give you a head’s up that there may be information, okay? She could not confirm there was an investigation” into Flynn.

In her testimony yesterday, Yates did not reveal how she came to know that Flynn had been in communication with the Russian ambassador, Sergey Kislyak, during the Trump transition. But the secret is not hard to guess: Yates was privy to intelligence that ultimately derived from electronic surveillance of Kislyak and/or other Russian officials. Flynn was caught up in the routine interception of foreign officials’ communications.

Yates claims she warned McGahn that Flynn could have been vulnerable to blackmail by the Kremlin, which knew he had not been honest when he led Vice President Pence to believe that he had never discussed sanctions with Russian officials. Eighteen days after Yates raised this concern with McGahn, Flynn resigned. Yates herself had been fired on January 30, after she publicly refused to let her department defend the president’s executive order on immigration from extremist hotspots in the Islamic world.

The entirety of the news excitement—"value” would hardly be the word—in Yates’s testimony concerns that eighteen-day gap between her statement to McGahn and Flynn’s departure. Did the Trump administration deliberately keep in place a national security advisor who was compromised by Russia, until the Washington Post revealed that he had lied to Pence?

If that’s what the story is meant to be, it has yet to be proved: there are other reasons, after all, why the administration may not have acted on Yates’s warning, starting with the fact that the White House was badly organized in general and just about to issue its controversial immigration order. The immigration order was signed January 27. Yates had met with McGahn January 25. She was fired January 30. During this period, Yates does not seem to have been terribly concerned to make sure the White House would take her seriously as a nonpolitical career civil servant. On the contrary, her stunt in opposing the president’s executive order was as clear a political statement as anything could be. The White House may have had cause to fire Flynn by then. But it could hardly have taken Yates’s good faith toward the administration or its personnel for granted—if Flynn was going to go, the White House needed proof of its own, not just accusations leveled by someone like Yates.

The White House has all along claimed that Democratic loyalists in the civil service and former Obama officials have been conniving to undermine President Trump’s administration. As it happens, mere hours before Yates’s testimony to the Senate, a cluster of anonymous Obama officials were cited as sources for news stories saying that Obama had personally warned Trump about Flynn two days after the election. What prompted these unnamed officials to speak out at this moment of moments? Again, it’s not hard to guess: politics. They were boosting Yates’s signal, amplifying the narrative that Trump had been scandalously irresponsible to let Flynn serve as national security advisor, however briefly.

What these Obama officials revealed, however, does nothing to reinforce Yates’s Russia-related testimony. "Obama passed along a general caution that he believed Flynn was not suitable for such a high level post,” NBC reported, citing one official. That advice came in the context of a larger discussion of personnel transition. Obama had, of course, fired Flynn as director of the Defense Intelligence Agency just a few years before: he had reasons for recommending against including him in the new administration that had nothing to do with any suspicion of foreign compromise on Flynn’s part.

Politics also explains why the Trump administration was so reluctant to fire Flynn. He had been a loyal soldier for Trump during the 2016 campaign, and the more right-wing elements in the administration have shown a penchant for loyalty: when Sebastian Gorka was recently on the brink of being pushed out of the White House, Steve Bannon and President Trump himself reportedly intervened to save him. Doubtless Trump and Bannon would have been even less eager to remove Flynn at Yates’s behest.

Trump did make a mistake by appointing Flynn as national security advisor. Flynn lied to Pence, and presumably to others. He discussed sanctions with Russia’s ambassador. Since "resigning,” he has retroactively registered as a foreign agent on behalf of Turkey. But Flynn has not been charged with or even credibly accused of any crime. After months of investigations and media hype, no Trump administration or campaign official has been accused of wrongdoing, and the president himself has yet to be implicated in any improper—or even unseemly—dealings with Russia. Foreign meddling in U.S. elections is matter that demands investigation, but so far this hunt for Kremlin stooges has turned up far less than the Whitewater investigations into Bill Clinton and his cronies did. Whatever work is to be done here is better left to the FBI than to partisan senators and activist civil servants.

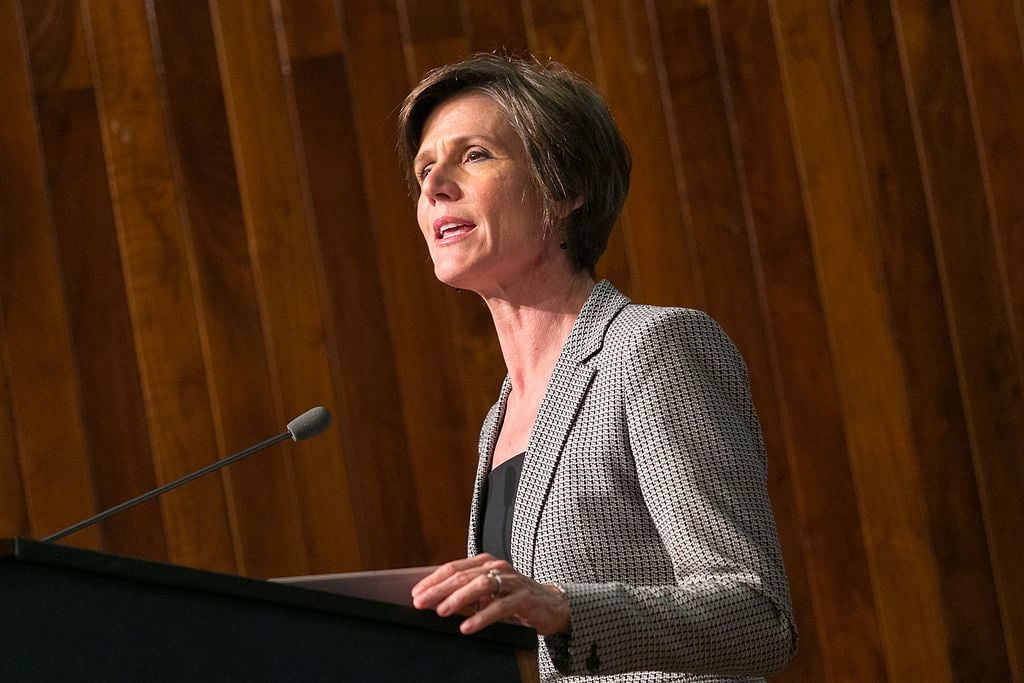

Image: Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates in April 2016. Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

.jpg/250px-ElbeDay1945_(NARA_ww2-121).jpg)