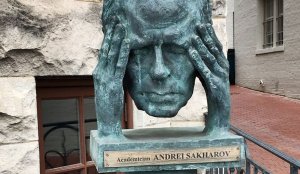

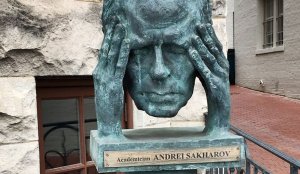

If the legendary scientist, peace and human rights activist Andrei Sakharov was alive today, he would have celebrated his 100th birthday earlier this year and we can imagine that he would be more than a little dismayed by the state of today’s world.

If the legendary scientist, peace and human rights activist Andrei Sakharov was alive today, he would have celebrated his 100th birthday earlier this year and we can imagine that he would be more than a little dismayed by the state of today’s world.

By Matthew Ehret and Edward Lozansky

If the legendary scientist, peace and human rights activist Andrei Sakharov was alive today, he would have celebrated his 100th birthday earlier this year and we can imagine that he would be more than a little dismayed by the state of today’s world.

Relations between the United States and Russia have fallen to their lowest point in decades, and a new Iron Curtain has begun to descend between NATO-affiliated states of the "rules-based international order” and the supposedly "authoritarian states” allied to the great Eurasian powers. Diplomatic bridge-burning has been occurring at ever faster rates as talk of nuclear war has become normalized throughout the halls of power in Europe and Washington.

When Sakharov died on December 14, 1989, hope for an age of peace and brotherhood was at an all-time high as the Cold War was finally coming to an end and the rigid dehumanizing system of the Soviet Union was about to be brushed into the dustbin of history.

The fact that only 30 years after this period of great hope, the world would again find itself on the precipice of nuclear annihilation would have been inconceivable.

Since creative thinking and courageous role models capable of challenging this race into nuclear oblivion appear to be lacking today, let us revisit the life’s work, mind and mission of Andrei Sakharov. Perhaps somewhere along the way during this exercise, we might find the ideas necessary to put out the flames of war threatening all of civilization.

An Overview of Sakharov’s Accomplishments and Struggles

Andrei Sakharov was a man of exceptional talent who distinguished himself on a multitude of scientific and humanitarian levels. On one hand, he was the inventor of the Soviet version of the most devastating thermonuclear weapon on earth: the H-bomb. But on the other hand, he was a peacemaker who advocated the ban for nuclear explosion testing in the atmosphere resulting in the 1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. His ideas were also instrumental in the design of "Tokamak” fusion reactors that redirect the vast power of the atom from the destructive effects of the H-bomb towards the production of nearly unlimited energy for peaceful purposes.

Sakharov’s intellect was matched only by his courage as he also became a leading peace and human rights activist by the mid-1960s and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize while being denounced and sent into internal exile by the Soviet government.

Despite the fact that his discoveries ushered into the world the most destructive weapon ever known to mankind, Sakharov was always motivated by the drive to establish more balance than terror knowing that any off set of this equation for too long would easily result in a cascading collapse into total annihilation. There was and still is no shortage of war hawks who believe that "limited” or even full-scale nuclear war was something that was worth risking in order to stop the spread of an opposing political ideology.

Sakharov was never one to fall into false polarizations of left vs. right and chose always to stand up for right vs. wrong. He kept calling for an end to the Cold War through U.S.-Russia scientific cooperation and economic development.

He was inspired by the wave of social change and rise in consciousness sweeping the globe. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s civil rights movement was sweeping the USA, as Robert Kennedy was emerging as a progressive leader picking up the torch of leadership that had fallen with his brother’s assassination. Closer to home, the seven-month long Prague Spring was launched, led by Alexander Dubcek. This process saw historic reforms imposed in Czechoslovakia that broke the rigid formula of "dictatorial communism” vs. "liberal capitalism.”

In 1968, this inspiration took the form of Sakharov’s great work Considerations about Progress and Human Rights which outlined his moral and political philosophy of government with both practical insights along with bold visionary pathways to a collective future.

Among the many themes raised in this powerful essay included the vital importance of cooperation on frontier science while applying the fruits of technological progress. Sakharov did battle with the rise in irrational fears of the atom which he rightfully understood as a vital ingredient to the solving of world poverty, just as he tackled the underappreciated problem of the stupefaction of mass culture which rendered society more pliable to the manipulation of a detached elite.

This undying belief in the moral and intellectual elevation of the masses alongside the widening of the hearts of the scientific intelligentsia could only occur when freedom of conscience would become a universal right both in theory and practice for all. For only then could scientists become unfettered by the chains of encrusted political machines and secret policing. When scientific leadership could become creatively free to express itself unbounded by fear and the pressures of immediate survival, Sakharov believed that the withholding of culture and scientific knowledge to a small, privileged elite would also come to an end, as mass cultural and scientific education could finally uplift the minds and morals of the people making true democracy a feasible goal. On this point, Sakharov stated: "Only universal cooperation under conditions of intellectual freedom and the lofty moral ideals of socialism and labor, accompanied by the elimination of dogmatism and pressures of the concealed interests of ruling classes, will preserve civilization. Freedom of thought is the only guarantee of the feasibility of a scientific democratic approach to politics, economy, and culture.”

This reciprocal dynamic was a vital ingredient to Sakharov’s faith that the world was destined to converge towards a synthesis of the best of both capitalist and socialist worlds.

Throughout the 1970s, Sakharov became a world champion of human rights being awarded the 1975 Nobel Peace Prize for his work defending prisoners of conscience held in labor camps, suffering the injustices of internal exile, censorship, secret courts and sometimes even worse. His passionate calls for the release of prisoners of conscience and his leading voice in new organizations like the Moscow Helsinki Group ensured his renown as a global role model for freedom lovers as well as an enemy of tyrants running the Soviet Politburo.

By 1980, just as the Soviet Union had begun to launch into its own "Vietnam” debacle in Afghanistan, and before he could emerge as a leading anti-Afghan war voice, Sakharov was stripped of all awards and sent off to internal exile in Gorky (today’s Nizhny-Novgorod) where he was isolated, deprived of scientific papers and kept under constant surveillance.

Despite this set back, Sakharov continued to find creative ways to bring his writings to the attention of the international community. Through the tireless efforts of many activists, President Ronald Reagan was informed and inspired to do something unprecedented. On May 12, 1983, President Reagan delivered a historic speech on the front lawn of the White House announcing Andrei Sakharov Day saying: "Andrei Sakharov‘s voice is not just the solitary voice of principle of one man with courage; it is also the free voice of his people — a great, good, and noble people who long for freedom and just rule.”

It is an irony of history that this year, no other statesman but President Vladimir Putin echoed Reagan’s words by saying, "we are truly proud that this outstanding scientist was our compatriot and contemporary.”

In 1986 Mikhail Gorbachev began his liberalizing reforms and Sakharov’s exile was ended as he was invited back to Moscow. Amidst this exciting period, in March 1989, Sakharov was elected to the parliament where he could finally play a more direct role in policy making as a gateway to manifesting his ideals on earth.

Sadly, he died on December 14 of that same year and his ideas for East-West transition from confrontation to alliance did not materialize. It can be argued without much exaggeration that the failure to advance his visionary ideas has resulted in the current lurch of mankind towards a looming nuclear catastrophe three decades after his passing.

Despite the many genuine promises for cooperation and economic development promoted by leading politicians, scientists, educators, businessmen, cultural figures in the West, the dissolution of the Soviet Union saw an unprecedented rise of unipolar military expansionism and economic looting.

Instead of a "new security architecture from Vancouver to Vladivostok” promised by George H. W. Bush, and the fact that the Cold War’s end should have rendered both NATO and MAD obsolete artifacts in the dustbin of history, the heirs of General Curtis "nuke the commies” LeMay lost no time in consolidating their power position by celebrating "the end of history” by accelerating NATO’s expansion across former Soviet space.

Instead of the prosperity promised by the transition from a planned to market economy driven by great projects, Russia got shock therapy en masse, as austerity and sweeping privatizations crippled the country on every level. Instead of true assistance, nearly all Russia received between 1992-2000 were numerous "advisors” who joined local oligarchs to rob the country and bring its economy into default.

Note what Washington Post columnist David Ignatius said in August 1999: ‘"What makes the Russian case so sad is that the Clinton administration may have squandered one of the most precious assets imaginable — which is the idealism and goodwill of the Russian people as they emerged from 70 years of Communist rule. The Russia debacle may haunt us for generations. Gore played a key role in that messy process, and he has a lot of explaining to do,” states Ignatius who also added evidence of "damning details of U.S. complicity in this process” cited by the Post’s former Moscow bureau chief, Robert Kaiser.’

Despite this historic irony, the Sakharov’s dream of a world of cooperation and peace might still find a place in our collective destiny. The threats facing humanity’s future and requiring creative cooperation between the USA and Russia certainly are not lacking. Not only does a renewed arms race with an increased lunge towards nuclear war shape the modern geopolitical age, but a global climate and health crisis also threatens our collective future. Asteroids continue to pose an existential challenge and the need to leap from fossil fuels into sustainable high-quality energy sources like fusion power remains our only hope for the long-term survival of the species.

New questions in cosmology and particle physics grasp the attention of scientists from all corners of the world and even here, the ideas of Sakharov offer valuable pathways, as his years of work on the development of a new physics of baryosynthesis and universal asymmetry offers great creative possibilities for the much-needed unification of micro and macro physics.

As we move into the new year, it is humbling to be reminded by so many experts who have sounded the alarm that the world is once again on the brink of WWIII. This is due to the events in Ukraine, as well as the dangerous sabre-rattling in the Pacific. Although the worst-case scenario has been luckily avoided so far, the war-mongering rhetoric is still around and it would be wise for everyone, and especially for the world’s leaders, to reread Sakharov’s works, and Reagan-Gorbachev conversations inspired by Sakharov when they agreed that nuclear war should never be fought.

Sakharov’s passionate calls for nations to face and solve numerous world problems through the sharing of advanced scientific and technological progress is at our fingertips, if only Washington and Moscow would implement his ideas of turning East-West relations from confrontation to cooperation in order to dace the world’s global challenges.

Mathew Ehret is Vice President of the Rising Tide Foundation and Senior Fellow of the American University in Moscow. Edward Lozansky, is President of the American University in Moscow.

.jpg/250px-ElbeDay1945_(NARA_ww2-121).jpg)